|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

Taxonomic paper

|

|

Corresponding author:

Academic editor: Fredric Govedich

Received: 30 Mar 2015 | Accepted: 23 Apr 2015 | Published: 27 Apr 2015

© 2015 Takafumi Nakano, Tatjana Dujsebayeva, Kanto Nishikawa

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Nakano T, Dujsebayeva T, Nishikawa K (2015) First record of Limnatis paluda (Hirudinida, Arhynchobdellida, Praobdellidae) from Kazakhstan, with comments on genetic diversity of Limnatis leeches. Biodiversity Data Journal 3: e5004. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.3.e5004

|

|

Abstract

Background

New information

Specimens of the genus Limnatis from Almaty Province, Kazakhstan are identified as Limnatis paluda. This is the first record of Limnatis paluda from Kazakhstan. Mitochondrial COI and 12S data demonstrated that the present specimens are genetically close to an Israeli specimen identified as Limnatis nilotica. In addition, molecular data suggest that some Limnatis specimens whose DNA sequences have been reported were misidentified. According to the observed phylogenetic relationships, the taxonomic status of the known Limnatis species should be revisited.

Keywords

Hirudinea, Hirudinida, Limnatis paluda, COI, 12S, genetic diversity, geographical record, Kazakhstan

Introduction

The genus Limnatis

The type locality of L. nilotica is Egypt, and this species has been reported to occur mainly in Middle Eastern countries (

Materials and methods

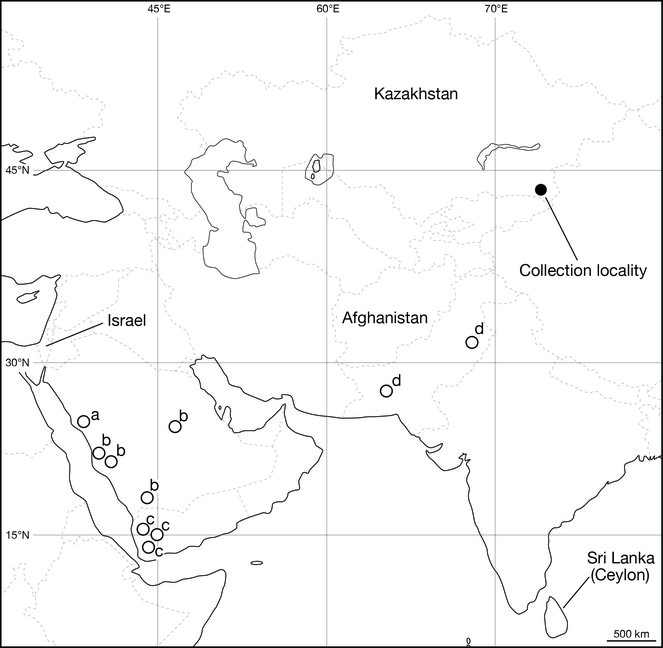

Leeches were collected from the Suygaty Valley located at the left bank part of the Ily River Depression, Almaty Province, Kazakhstan (Fig.

The numbering convention is based on

Sequences of mitochondrial COI as well as 12S, tRNAVal and 16S (12S–16S) were determined for 2 specimens from Almaty Province. The extraction of genomic DNA and DNA sequencing methods followed

To determine the phylogenetic position of Kazakhstani Limnatis, 10 previously published sequences were obtained from the INSDC for use in molecular phylogenetic analyses (Table

Samples with voucher or isolate numbers, collection country and INSDC accession numbers used for molecular analyses. Sequences marked with an asterisk (*) were obtained for the first time in the present study. Acronym: KUZ, Zoological Collection of Kyoto University. Sources: a

| Species (voucher or isolate #) | Country | COI | 12S–16S or 12S | ||

| Accession # | Length | Accession # | Length | ||

| Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z702) | Kazakhstan | AB981654 * | 1267 | AB981653 * | 601 |

| Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z703) | Kazakhstan | AB981656 * | 1267 | AB981655 * | 601 |

| Limnatis paluda (AFLP) | Afghanistan | GQ368755 | 658 | ||

| Limnatis nilotica | Israela | AY425452 | 648 | AY425430 | 353 |

| Limnatis cf. nilotica (AOBS) | Namibia | GQ368754 | 565 | GQ368815 | 355 |

| Limnatis nilotica | Bosnia | GQ368814 | 355 | ||

| Limnatis cf. nilotica | Croatiab | AY763152 | 631 | AY763161 | 503 |

| Limnobdella mexicana (LM117) | Mexico | GQ368758 | 658 | GQ368818 | 353 |

Sequences of mitochondrial COI were aligned by eye, as no indels were observed. Mitochondrial 12S–16S sequences were aligned using MAFFT v. 7.213 FFT-NS-2 (

Taxon treatment

Limnatis paluda

-

scientificName: Limnatis paluda (Tennent, 1859); country:Kazakhstan; stateProvince:Almaty; verbatimLocality:Suygaty Valley, Almaty Province, Kazakhstan; decimalLatitude:43.512778; decimalLongitude:78.9708331; eventDate:2013-06-21; individualCount:1; sex:hermaphrodite; catalogNumber:Z700; recordedBy:Kanto Nishikawa; identifiedBy:Takafumi Nakano; institutionCode:KUZ

-

scientificName: Limnatis paluda (Tennent, 1859); country:Kazakhstan; stateProvince:Almaty; verbatimLocality:Suygaty Valley, Almaty Province, Kazakhstan; decimalLatitude:43.512778; decimalLongitude:78.9708331; eventDate:2013-06-21; individualCount:1; sex:hermaphrodite; catalogNumber:Z701; recordedBy:Kanto Nishikawa; identifiedBy:Takafumi Nakano; institutionCode:KUZ

-

scientificName: Limnatis paluda (Tennent, 1859); country:Kazakhstan; stateProvince:Almaty; verbatimLocality:Suygaty Valley, Almaty Province, Kazakhstan; decimalLatitude:43.512778; decimalLongitude:78.9708331; eventDate:2013-06-21; individualCount:1; sex:hermaphrodite; catalogNumber:Z702; recordedBy:Kanto Nishikawa; identifiedBy:Takafumi Nakano; institutionCode:KUZ

-

scientificName: Limnatis paluda (Tennent, 1859); country:Kazakhstan; stateProvince:Almaty; verbatimLocality:Suygaty Valley, Almaty Province, Kazakhstan; decimalLatitude:43.512778; decimalLongitude:78.9708331; eventDate:2013-06-21; individualCount:1; sex:hermaphrodite; catalogNumber:Z703; recordedBy:Kanto Nishikawa; identifiedBy:Takafumi Nakano; institutionCode:KUZ

Description

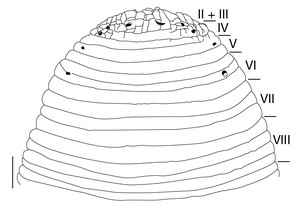

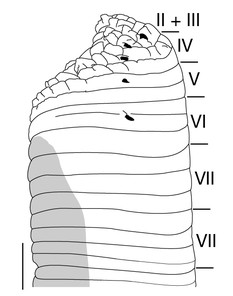

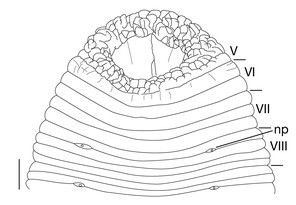

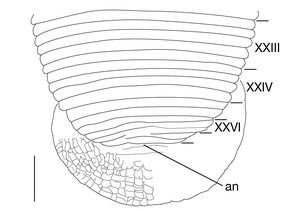

Body firm, muscular, with constant width in caudal direction, dorsoventrally compressed, BL 22.64–36.73 mm, BW 4.47–9.82 mm (Fig.

Somite I completely merged with prostomium (Fig.

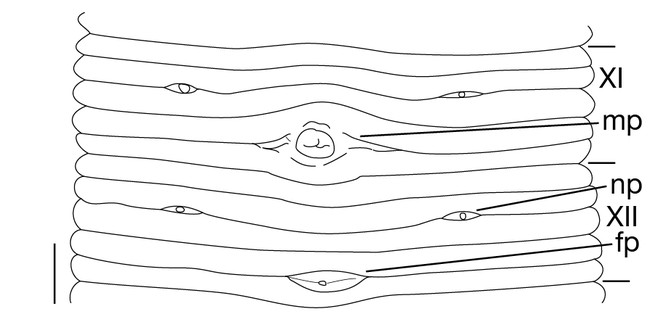

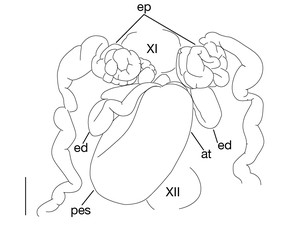

Male gonopore in XI b5/b6 (Fig.

Eyes 5 pairs, in parabolic arc; 1st and 2nd pairs on II + III, 3rd pair on IV (a1 + a2), 4th pair on V (a1 + a2), and 5th pair on VI a2 (Fig.

In 17 pairs, one each situated ventrally at posterior margin of VIII a1 and b2 of each somite in IX–XXIV (Figs

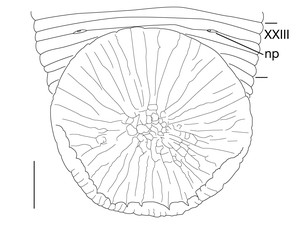

1 median longitudinal furrow on ventral surface of oral sucker (Fig.

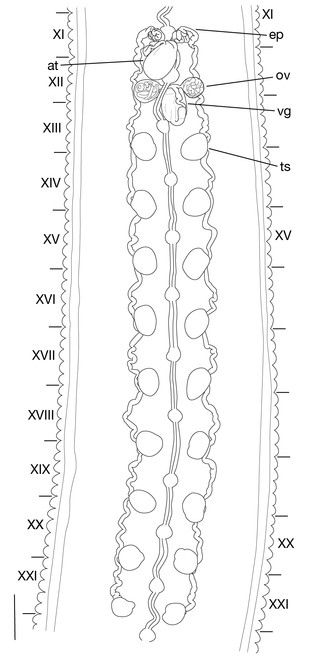

Testisacs 8 or 9 pairs (Fig.

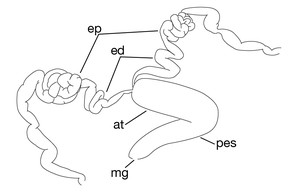

Limnatis paluda (

b: left lateral view of schematic drawing of male median reproductive system.

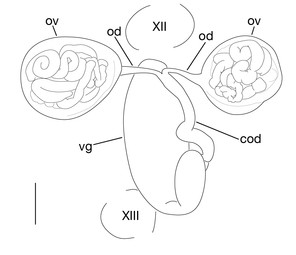

Pair of ovisacs globular, in XII b5–XIII b1 (Figs

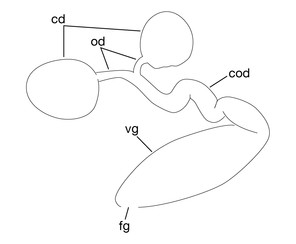

Limnatis paluda (

b: left lateral view of schematic drawing of female reproductive system.

When alive, dorsal surface uniform reddish brown (Fig.

Habitat

During night time, the leeches examined in this study were found crawling in a small pond (Figs

Genetic data

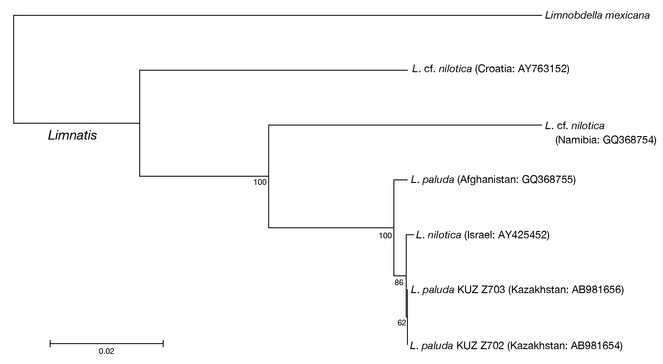

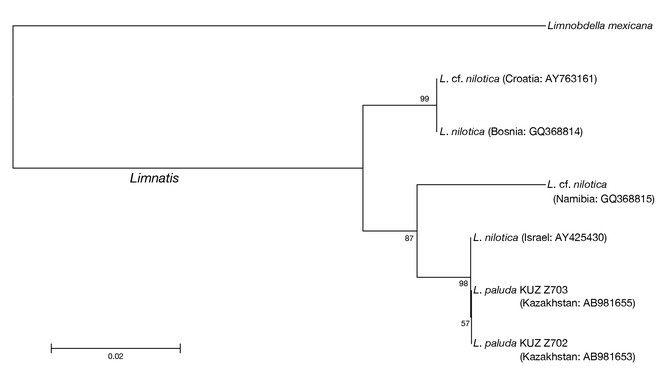

Neighbour-joining trees generated based on both the COI (Fig.

The COI uncorrected p-distance between the Kazakhstani L. paluda and the Israeli L. nilotica was 0.2% (Table

Uncorrected p-distances for available COI sequences of Limnatis leeches. Length of each sequence is listed in Table

| Species | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z702) | Kazakhstan | ||||||

| 2. Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z703) | Kazakhstan | 0.000 | |||||

| 3. Limnatis nilotica | Israel | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||||

| 4. Limnatis paluda | Afghanistan | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | |||

| 5. Limnatis cf. nilotica | Namibia | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.074 | ||

| 6. Limnatis cf. nilotica | Croatia | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.097 | 0.092 | 0.119 |

Uncorrected p-distances for available 12S sequences of Limnatis leeches. Length of each sequence is listed in Table

| Species | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z702) | Kazakhstan | ||||||

| 2. Limnatis paluda (KUZ Z703) | Kazakhstan | 0.000 | |||||

| 3. Limnatis nilotica | Israel | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| 4. Limnatis cf. nilotica | Namibia | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.028 | |||

| 5. Limnatis nilotica | Bosnia | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.039 | ||

| 6. Limnatis cf. nilotica | Croatia | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.039 | 0.000 |

Taxon discussion

The present 4 specimens of Limnatis clearly belong to Limnatis paluda sensu

As mentioned above, the taxonomic identities of Limnatis species have not been fully settled. According to the present neighbour-joining trees and p-distance data, however, the Israeli Limnatis leech, of which DNA sequences have been deposited with INSDC, should be assigned to Limnatis paluda as mentioned in (

It is noteworthy that the specimens of Limnatis paluda analysed in this study have low genetic divergences (0.2–0.5% in COI and 0% in 12S). The COI uncorrected p-distances between the present Kazakhstani specimens and the Israeli specimen are lower than that between the former and the Afghan specimen (0.5%) and that between the latter and the Afghan L. paluda (0.6%). The collection locality in Kazakhstan is ca. 4,000 km from Israel, and ca. 2,000 km from Afghanistan. In contrast, Israel is at most ca. 3,500 km from Afghanistan. Because few DNA sequences of L. paluda are available, it may be difficult to reveal its detailed genetic structure. However, the results of the mitochondrial genetic analyses at least shed light on the discordance between the COI genetic divergence between the Kazakhstani L. paluda and the Israeli specimen and the geographic distance between the collection localities.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Andrey Kovalenko and Mr Oleg Okshin for their assistance in the field in Kazakhstan, Dr Atushi Tominaga (University of the Ryukyus) for providing a picture of the leech habitat, and Dr Bonnie Bain (Southern Utah University), Dr Serge Y. Utevsky (V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University) and Dr Fredric R. Govedich (Southern Utah University) for their constructive comments on this manuscript. This study was conducted as part of research collaboration between Kyoto University and the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (General Memorandum for Scientific Cooperation and Exchange, 4 March 2013), and was financially supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows to TN, and that for Young Scientists (B) to TN (#26840127) as well as to KN (#23770084).

References

- Internal hirudiniasis in man with Limnatis nilotica, in Iraq.The Journal of Parasitology54(3):637‑638. https://doi.org/10.2307/3277105

- Freshwater leeches from Yemen.Hydrobiologia263(3):185‑190. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00006269

- Leech (Limnatis nilotica) parasitation in wild red deer (Cervus elaphus) in west Sierra Morena (Spain).Erkrankungen der Zootiere35:209‑211.

- The Medieval Towns of Kazakstan along the Great Silk Road.Gylym,Almaty,216pp. [InRussian]. [ISBN5-628-02237-3]

- Révision de Hirudinées du Musée de Turin.Bollettino dei Musei di Zoologia ed Anatomia Comparata della R. Università di Torino8(145):1‑32.

- Arhynchobdellida (Annelida: Oligochaeta: Hirudinida): phylogenetic relationships and evolution.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution30(1):213‑225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2003.09.002

- Occurrence of the leech Limnatis paluda as a respiratory parasite in man: case report from Saudi Arabia.Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene97(1):18‑20.

- Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap.Evolution39(4):783‑791. https://doi.org/10.2307/2408678

- DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates.Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology3(5):294‑299.

- Note on leeches sent by Dr E. W. G. Masterman from Palestine.Parasitology1(4):282‑283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000003553

- Note on the leech Limnatis nilotica.Records of the Indian Museum18:213‑214.

- MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability.Molecular Biology and Evolution30(4):772‑780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010

- Kinzelbach R, Rückert F (1985) Annelida of Saudi Arabia. The leeches (Hirudinea) of Saudi Arabia. In: Büttiker W, Krupp F (Eds) Fauna of Saudi Arabia.6.Pro Entomologia c/o Natural History Museum,Basle. [ISBN3-7234-0005-1].

- Comparative structural analysis of jaws of selected blood-feeding and predacious arhynchobdellid leeches (Annelida: Clitellata: Hirudinida).Zoomorphology134(1):33‑43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-014-0245-4

- Helminths of vertebrates and leeches taken by the U.S. Naval Medical Mission to Yemen, Southwest Arabia.Canadian Journal of Zoology46(5):1071‑1075. https://doi.org/10.1139/z68-149

- Fauna of Ukraine. Leech.30.Academy of Science of the Ukrainian SSR,Kiev,196pp. [InUkrainian].

- Fauna USSR. Leeches.Nauka,Leningrad,484pp. [InRussian].

- A new species of leech Limnatis bacescui sp. nov. (Hirudinoidea: Hirudinidae).Revue Roumaine de Biologie, Série de Zoologie17(4):237‑239.

- Moore JP (1927) Arhynchobdellæ. In: Harding WA, Moore JP. The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Hirudinea.Taylor & Francis,London.

- Moore JP (1927) The segmentation (metamerism and annulation) of the Hirudinea. In: Harding WA, Moore JP. The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Hirudinea.Taylor & Francis,London.

- Monographie de la Famille des Hirudinées.Maison de Commerce,Montpellier,152pp.

- A new species of Orobdella (Hirudinida, Arhynchobdellida, Gastrostomobdellidae) and redescription of O. kawakatsuorum from Hokkaido, Japan with the phylogenetic position of the new species.ZooKeys169:9‑30. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.169.2425

- First record of Limnatis nilotica from Oman (Hirudinea: Hirudinidae).Miscellanea Zoologica Hungarica11:11‑14.

- Tyrannobdella rex n. gen. n. sp. and the evolutionary origins of mucosal leech infestations.PLoS ONE5(4):e10057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010057

- Poly-paraphyly of Hirudinidae: many lineages of medicinal leeches.BMC Evolutionary Biology9:246. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-246

- Egel aus den Levante-Ländern (Clitellata: Hirudinea).Senckenbergiana Biologica66:135‑152.

- Savigny MJC (1822) Système des Annelides, principalement de celles des côtes de l'Égypte et de la Syrie, offrant les caractères tant distinctifs que naturels des ordes, familles et genres avec la description des espèces. In: Savigny MJC. Description de l'Égypte, ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française. Histoire Naturelle.Imprimerie Impériale,Paris. URL: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/128879#page/423/mode/1up

- Leech Biology and Behaviour.Clarendon Press,Oxford,1065pp.

- Identification key to the leech (Hirudinoidea) genera of the world, with a catalogue of the species. V. Family: Hirudinidae.Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae15:151‑201.

- MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0.Molecular Biology and Evolution30(12):2725‑2729. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst197

- Ceylon: An Account of the Island, Physical, Historical, and Topographical with Notices of its Natural History, Antiquities and Productions.1st edition,1.Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts,London,619pp.

- Celebrity with a neglected taxonomy: molecular systematics of the medicinal leech (genus Hirudo).Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution34(3):616‑624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2004.10.012

- Phylogeny and phylogeography of medicinal leeches (genus Hirudo): Fast dispersal and shallow genetic structure.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution63(2):475‑485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.01.022

- A case of human ophthalmohirudinosis.Annals of Ophthalmology106(1):66. [InRussian].