|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

Data Paper (Biosciences)

|

|

Corresponding author:

Academic editor: Miguel Alonso-Zarazaga

Received: 12 Oct 2015 | Accepted: 08 Dec 2015 | Published: 10 Dec 2015

© 2015 Michael Skvarla, Danielle Fisher, Kyle Schnepp, Ashley Dowling

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Skvarla M, Fisher D, Schnepp K, Dowling A (2015) Terrestrial arthropods of Steel Creek, Buffalo National River, Arkansas. I. Select beetles (Coleoptera: Buprestidae, Carabidae, Cerambycidae, Curculionoidea excluding Scolytinae). Biodiversity Data Journal 3: e6832. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.3.e6832

|

|

Abstract

Background

The Ozark Mountains are a region with high endemism and biodiversity, yet few invertebrate inventories have been made and few sites extensively studied. We surveyed a site near Steel Creek Campground, along the Buffalo National River in Arkansas, using twelve trap types – Malaise traps, canopy traps (upper and lower collector), Lindgren multifunnel traps (black, green, and purple), pan traps (blue, purple, red, white, and yellow), and pitfall traps – and Berlese-Tullgren extraction for eight and half months.

New information

We provide collection records of beetle species belonging to eight families collected at the site. Thirty one species represent new state records: (Buprestidae) Actenodes acornis, Agrilus cephalicus, Agrilus ohioensis, Agrilus paracelti, Taphrocerus nicolayi; (Carabidae) Agonum punctiforme, Synuchus impunctatus; (Curculionidae) Acalles clavatus, Acalles minutissimus, Acoptus suturalis, Anthonomus juniperinus, Anametis granulata, Idiostethus subcalvus, Eudociminus mannerheimii, Madarellus undulatus, Magdalis armicollis, Magdalis barbita, Mecinus pascuorum, Myrmex chevrolatii, Myrmex myrmex, Nicentrus lecontei, Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus, Piazorhinus pictus, Phyllotrox ferrugineus, Plocamus hispidulus, Pseudobaris nigrina, Pseudopentarthrum simplex, Rhinoncus pericarpius, Sitona lineatus, Stenoscelis brevis, Tomolips quericola. Additionally, three endemic carabids, two of which are known only from the type series, were collected.

Keywords

Anthribidae, Attelabidae, Brachyceridae, Brentidae, Buprestidae, Carabidae, Cerambycidae, Curculionidae, state record, range expansion, endemic, Interior Highlands, Boston Mountains

Introduction

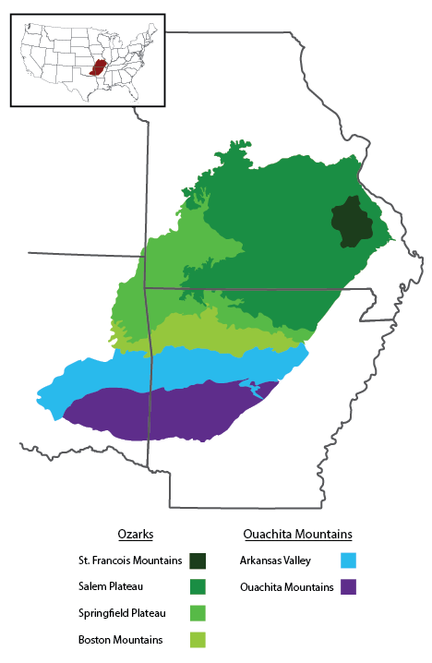

The Interior Highlands is a mountainous physiogeographic division in the central United States and the only significant topographic relief between the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains (Fig.

The Ouachita Mountains are east-west trending fold mountains approximately 100 km wide and 190 km long (3,237,600 ha), with elevations up to 818 m (

Prior to European settlement, the Ouachita Mountains were dominated by shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.), pine-hardwood, and mixed oak (Quercus L.) forests, with diverse, fire-dependent forb and grass understories (

The Ozarks, also referred to as the Ozark Mountains or Ozark Plateau, is divided into four geologic subdivisions. The Saint Francois Mountains, the oldest subdivision, is the exposed remains of a Proterozoic mountain range that formed through volcanic and intrusive activity 1485 Ma (

The Salem and Springfield Plateaus rise to elevations of 450 m and 550 m, respectively, and are characterized by relatively flat plateau surfaces that form extensive plains cut into rolling, level-topped hills around rivers and other flowing water (

The Ouachita Mountains and Ozarks have never been connected as the Arkansas Valley (also called the Arkansas River Valley), which is part of the Arkoma Basin, formed as a foreland basin through downwarping along the Ouachita orogeny when the Ouachita Mountains were uplifted (

The Interior Highlands can also be divided by ecoregion. Ecoregions, as defined by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, are divided into three levels: Level I is the most inclusive and places the region "in context at global or intercontinental scales"; Level II regions are subdivisions of Level I regions and are "intended to provide a more detailed description of the large ecological areas nested within the level I regions"; finally, Level III has the smallest subdivisions that "enhance regional environmental monitoring, assessment and reporting, as well as decision-making" and "allow locally defining characteristics to be identified, and more specifically oriented management strategies to be formulated" (

As may be expected with the regions inclusion in the Level I Eastern Temperate Forests ecoregion, many species found in the Interior Highlands are typical of eastern North America. However, some western species reach their eastern range limit in the Interior Highlands (e.g., Texas brown tarantula [Aphonopelma hentzi (Jean-Étienne Girard, 1852)], eastern collared lizard [Crotaphytus collaris (Say, 1823)], western diamondback rattlesnake [Crotalus atrox Baird & Girard, 1853]); these species likely colonized the Interior Highlands during the post-glacial Xerothermic Interval (6,000-4,000 b.p.), during which time prairies and xeric habitat similar to that in the west expanded into the Interior Highlands, and remained after the climate became more moist (

Select references to recently discovered and described species with disjunct and endemic distributions in the Interior Highlands.

| Range status | Taxonomic category | Select references |

| Disjunct | lichens |

|

| plants |

|

|

| molluscs |

|

|

| arthropods |

|

|

| fish |

|

|

| Endemic | lichens |

|

| plants |

|

|

| arthropods |

|

|

| fish |

|

Aquatic insects and crayfish have been relatively well surveyed within the Interior Highlands (Table

Select references for well-sampled aquatic arthropods in the Interior Highlands.

| Taxon | Select references |

| Ephemeroptera |

|

| Plecoptera |

|

| Trichoptera |

|

| Astacoidea |

|

Sampling methods

The following traps were maintained within the site: five Malaise traps (MegaView Science Co., Ltd., Taichung, Taiwan), twenty-five pan traps (five of each color: blue, purple, red, yellow, white) which were randomly arranged under the Malaise traps (one of each color per Malaise trap) so as to also act as intercept traps; fifteen Lindgren multi-funnel traps (ChemTich International, S.A., Heredia, Costa Rica) (five of each color: black, green, purple); four SLAM (Sea, Land, and Air Malaise) traps (MegaView Science Co., Ltd., Taichung, Taiwan) with top and bottom collectors that acted as canopy traps; and seventeen pitfall trap sets. Sixteen of the seventeen pitfall sets were placed in two transects of sets spaced every five meters centered on two Malaise traps while the final set was placed away from other traps. Additionally, ten leaf litter samples were collected for Berlese extraction when traps were serviced.

Pitfall traps were based on a design proposed by

Berlese-Tullgren samples were collected from a variety of habitats, including thin leaf litter away from objects; thick leaf litter accumulated along logs and rocks; moss; tree holes; bark from fallen, partially decayed trees; and bark and leaf litter accumulated at the base of standing, dead trees. An attempt was made to collect moist, non-desiccated litter in order to increase the number of specimens collected; this resulted in fewer samples being taken from thin leaf litter, moss, and tree bark during the hot, dry summer months. Tree holes were sampled once each so as not to totally destroy them as potential habitat; as the number of tree holes within the site was limited, this resulted in only a handful of collections from this habitat type. Leaf litter samples were processed for four to seven days until the litter was thoroughly dry using modified Berlese-Tullgren funnels.

Trap placement began on 8 March 2013 and all traps were set by 13 March 2013, except Lindgren funnels, which were set on 1 April 2013. Traps set earlier than 13 March were reset on that date in order to standardize trap catch between traps. Traps were serviced approximately every two weeks (Table

| Collection period |

| 13 March 2013 – 1 April 2013 |

| 1 April 2013 – 13 April 2013 |

| 30 April 2013 – 15 May 2013 |

| 15 May 2013 – 29 May 2013 |

| 29 May 2013 – 12 June 2013 |

| 12 June 2013 – 28 June 2013 |

| 28 June 2013 – 17 July 2013 |

| 17 July 2013 – 30 July 2013 |

| 30 July 2013 – 13 August 2013 |

| 13 August 2013 – 28 August 2013 |

| 28 August 2013 – 11 September 2013 |

| 11 September 2013 – 25 September 2013 |

| 25 September 2013 – 8 October 2013 |

| 8 October 2013 – 23 October 2013 |

| 23 October 2013 – 6 November 2013 |

| 6 Novemver 2013 – 20 November 2013 |

| 20 November 2013 – 4 December 2013 |

Maximum number of traps collected (canopy, Lindgren funnel, Malaise, pan, and pitfall traps) or collections made (Berlese-Tullgren) per collecting period and total number of samples per sampling type; traps were occasionally destroyed or otherwise lost during the 2-week sampling period.

| Trap type | Number of traps or collections | Number of samples |

| Berlese-Tullgren | 10 | 140 |

| Canopy trap (lower) | 4 | 72 |

| Canopy trap (upper) | 4 | 72 |

| Lindgren funnel (black) | 5 | 85 |

| Lindgren funnel (green) | 5 | 85 |

| Lindgren funnel (purple) | 5 | 82 |

| Malaise trap | 5 | 95 |

| Pan trap (blue) | 5 | 82 |

| Pan trap (purple) | 5 | 81 |

| Pan trap (red) | 5 | 83 |

| Pan trap (white) | 5 | 83 |

| Pan trap (yellow) | 5 | 83 |

| Pitfall | 17 | 268 |

Propylene glycol (Peak RV & Marine Antifreeze) (Old World Industries, LLC, Northbrook, IL) was used as the preservative in all traps as it is non-toxic and generally preserves specimens well (

Samples were coarse-sorted using a Leica MZ16 stereomicroscope illuminated with a Leica KL1500 LCD light source and a Wild M38 stereomicroscope illuminated with an Applied Scientific Devices Corp. Eco-light 20 fiber optic light source. After sorting, specimens were stored individually or by family in 2 mL microtubes (VWR International, LLC, Randor, PA) in 70% ethanol. Hard-bodied specimens (e.g., Carabidae, Curculionidae) were pinned or pointed as appropriate.

Specimens were identified with the use of published keys (Table

| Family | Genus | Reference |

| Anthribidae |

|

|

| Attelabidae |

|

|

| Brentidae |

|

|

| Buprestidae |

|

|

| Carabidae |

|

|

| Carabidae | Abacidus |

|

| Carabidae | Agonum |

|

| Carabidae | Anisodactylus |

|

| Carabidae | Brachinus |

|

| Carabidae | Calathus |

|

| Carabidae | Carabus |

|

| Carabidae | Chlaenius |

|

| Carabidae | Clinidium |

|

| Carabidae | Clivina |

|

| Carabidae | Cychrus |

|

| Carabidae | Cymindis |

|

| Carabidae | Dicaelus |

|

| Carabidae | Dicheirus |

|

| Carabidae | Harpalus |

|

| Carabidae | Lebia |

|

| Carabidae | Notiophilus |

|

| Carabidae | Notobia |

|

| Carabidae | Platynus |

|

| Carabidae | Progaleritina |

|

| Carabidae | Pseudophonus |

|

| Carabidae | Pterostichus |

|

| Carabidae | Rhadinae |

|

| Carabidae | Scaphinotus |

|

| Carabidae | Stenolophus |

|

| Carabidae | Tachyta |

|

| Cerambycidae |

|

|

| Cerambycidae | Astylopsis |

|

| Cerambycidae | Purpuricenus |

|

| Cerambycidae | Saperda |

|

| Curculionidae |

|

|

| Curculionidae | Cercopeus |

|

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus |

|

| Curculionidae | Cossonus |

|

| Curculionidae | Curculio |

|

| Curculionidae | Dichoxenus |

|

| Curculionidae | Eubulus |

|

| Curculionidae | Geraeus |

|

| Curculionidae | Lechriops |

|

| Curculionidae | Linogeraeus |

|

| Curculionidae | Lissorhoptrus |

|

| Curculionidae | Lymantes |

|

| Curculionidae | Notiodes |

|

| Curculionidae | Oopterinus |

|

| Curculionidae | Otiorhynchus |

|

| Curculionidae | Pandeletius |

|

| Curculionidae | Rhinoncus |

|

| Curculionidae | Tychius |

|

| Curculionidae | Tyloderma |

|

The sole representative of Lymantes (Curculionidae) collected keys to L. sandersoni in

Ormiscus (Curculionidae) consists of 14 described and approximately 30 undescribed species in North America north of Mexico (

Two weevil species, Auleutes nebulosus and Laemosaccus nephele (Curculionidae), are thought to be complexes of multiple cryptic species that are in need of revision (

The males of nine of 17 species of Cercopeus (Curculionidae) in the United States, including the widespread species C. chrysorrhoeus, are undescribed (

The Chrysobothris femorata (Buprestidae) species group consists of a dozen species that are difficult to seperate (with the exception of C. adelpha) as the characters used to distinguish species, including genitalia, are variable and often intermediate between species (

All specimens have been deposited in the University of Arkansas Arthropod Museum (UAAM), with the following exceptions: 1) 1–5 exemplars of each species have been deposited in the Dowling Lab Collection at the University of Arkansas; 2) the following specimens were sent to Peter Messer for identification confirmation and have been deposited in the P. W. Messer Collection: Agonum striatopunctatum (MS 13-0529-072, #136215; MS 13-0612-022, #139663), Cicindela rufiventris (MS 13-0717-001, #134492), Cyclotrachelus incisus (MS 13-0413-023, #139591; MS 13-0413-019, #139592; MS 13-0413-006, #139594; MS 13-1008-075, #139596), Cyclotrachelus parasodalis (MS 13-0430-019, #131983; MS 13-0529-037, #135057; MS 13-1106-002, #138280), Lophoglossus haldemanni (MS 13-0529-066, #135053), Pterostichus punctiventris (MS 13-0401-018, #135065; MS 13-1023-021, # 136216), Rhadine ozarkensis (MS 13-0925-027, #134547), Scaphinotus fissicollis (MS 13-1106-037, #137830), Selenophorus ellipticus (MS 13-0925-005, #136223), Selenophorus opalinus (MS 13-0813-034, # 136217), Trichotichus autumnalis (MS 13-0730-005, #136226), Trichotichnus vulpeculus (MS 13-0911-027, #136218).

New Arkansas state records for Buprestidae are based on the range data given by

Geographic coverage

The survey was conducted at 4 hectare plot established at Steel Creek along the Buffalo National River in Newton County, Arkansas, centered at approximately N 36°02.269', W 93°20.434'. The site is primarily 80–100 year old mature second-growth Eastern mixed deciduous forest dominated by oak (Quercus) and hickory (Carya), though American beech (Fagus grandifolia) and eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) are also abundant. A small (14 m x 30 m), fishless pond and glade (10 m x 30 m) with sparse grasses are present within the boundaries of the site.

36.0367 and 36.0397 Latitude; -93.3917 and -93.3397 Longitude.

Taxonomic coverage

All specimens of Anthribidae, Attelabidae, Brachyceridae, Brentidae, Buprestidae, Carabidae, Cerambycidae, Curculionidae excluding Scolytinae were identified to species.

Usage rights

Data resources

| Column label | Column description |

|---|---|

| typeStatus | Nomenclatural type applied to the record |

| catalogNumber | Unique within-project and within-lab number applied to the record |

| recordedBy | Who recorded the record information |

| individualCount | The number of specimens contained within the record |

| lifeStage | Life stage of the specimens contained within the record |

| kingdom | Kingdom name |

| phylum | Phylum name |

| class | Class name |

| order | Order name |

| family | Family name |

| genus | Genus name |

| specificEpithet | Specific epithet |

| scientificNameAuthorship | Name of the author of the lowest taxon rank included in the record |

| scientificName | Complete scientific name including author and year |

| taxonRank | Lowest taxonomic rank of the record |

| country | Country in which the record was collected |

| countryCode | Two-letter country code |

| stateProvince | State in which the record was collected |

| county | County in which the record was collected |

| municipality | Closest municipality to where the record was collected |

| locality | Description of the specific locality where the record was collected |

| verbatimElevation | Average elevation of the field site in meters |

| verbatimCoordinates | Approximate center point coordinates of the field site in GPS coordinates |

| verbatiumLatitude | Approximate center point latitude of the field site in GPS coordinates |

| verbatimLongitude | Approximate center point longitude of the field site in GPS coordinates |

| decimalLatitude | Approximate center point latitude of the field site in decimal degrees |

| decimalLongitude | Approximate center point longitude of the field site in decimal degrees |

| georeferenceProtocol | Protocol by which the coordinates were taken |

| identifiedBy | Who identified the record |

| eventDate | Date or date range the record was collected |

| habitat | Description of the habitat |

| language | Two-letter abbreviation of the language in which the data and labels are recorded |

| institutionCode | Name of the institution where the specimens are deposited |

| basisofRecord | The specific nature of the record |

Additional information

Analysis

8,048 specimens representing 251 species and 188 genera were collected during this study (Table

Species collected, including total number of specimens. New state records are indicated by an an asterisk (*).

| *Family | Genus | Species | Total specimens collected |

| Anthribidae | Euparius | Euparius marmoreus | 11 |

| Anthribidae | Eurymycter | Eurymycter fasciatus | 2 |

| Anthribidae | Ormiscus | 1 | |

| Anthribidae | Toxonotus | Toxonotus cornutus | 1 |

| Attelabidae | Eugnamptus | Eugnamptus angustatus | 12 |

| Attelabidae | Synolabus | Synolabus bipustulatus | 1 |

| Attelabidae | Temnocerus | Temnocerus aeratus | 6 |

| Brachyceridae | Notiodes | Notiodes limatulus | 1 |

| Brentidae | Arrhenodes | Arrhenodes minutus | 6 |

| Buprestidae | Acmaeodera | Acmaeodera tubulus | 70 |

| Buprestidae | Acmaeodera | Acmaeodera pulchella | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Actenodes | Actenodes acornis* | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus arcuatus complex | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus bilineatus | 35 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus cephalicus* | 18 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus defectus | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus fallax | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus geminatus | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus lecontei | 4 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus masculinus | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus ohioensis* | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus olentangyi | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus obsoletoguttatus | 12 |

| Buprestidae | Agrilus | Agrilus paracelti* | 3 |

| Buprestidae | Anthaxia | Anthaxia viridifrons | 6 |

| Buprestidae | Brachys | Brachys aerosus | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Chrysobothris | Chrysobothris adelpha | 60 |

| Buprestidae | Chrysobothris | Chrysobothris femorata complex | 70 |

| Buprestidae | Chrysobothris | Chrysobothris sexsignata | 7 |

| Buprestidae | Dicerca | Dicerca divaricata | 3 |

| Buprestidae | Dicerca | Dicerca lurida | 58 |

| Buprestidae | Dicerca | Dicerca obscura | 8 |

| Buprestidae | Dicerca | Dicerca spreta | 1 |

| Buprestidae | Ptosima | Ptosima gibbicollis | 5 |

| Buprestidae | Taphrocerus | Taphocerus gracilis | 3 |

| Buprestidae | Taphrocerus | Taphrocerus nicolayi* | 2 |

| Carabidae | Agonoleptus | Agonoleptus conjunctus | 17 |

| Carabidae | Agonum | Agonum punctiforme* | 2 |

| Carabidae | Agonum | Agonum striatopunctatum | 3 |

| Carabidae | Amara | Amara aenea | 3 |

| Carabidae | Amara | Amara cupreolata | 14 |

| Carabidae | Amara | Amara musculis | 30 |

| Carabidae | Anisodactylus | Anisodactylus rusticus | 33 |

| Carabidae | Apenes | Apenes sinuata | 8 |

| Carabidae | Badister | Badister notatus | 3 |

| Carabidae | Bembidion | Bembidion affine | 6 |

| Carabidae | Bembidion | Bembidion rapidum | 2 |

| Carabidae | Brachinus | Brachinus americanus | 91 |

| Carabidae | Calathus | Calathus opaculus | 14 |

| Carabidae | Calleida | Calleida viridipennis | 8 |

| Carabidae | Carabus | Carabus sylvosus | 20 |

| Carabidae | Chlaenius | Chlaenius platyderus | 1 |

| Carabidae | Chlaenius | Chlaenius tomentosus | 3 |

| Carabidae | Cicindela | Cicindela rufiventris | 3 |

| Carabidae | Cicindela | Cicindela sexguttata | 32 |

| Carabidae | Clinidium | Clinidium sculptile | 1 |

| Carabidae | Clivina | Clivina pallida | 1 |

| Carabidae | Cyclotrachelus | Cyclotrachelus incisus | 797 |

| Carabidae | Cyclotrachelus | Cylotrachelus parasodalis | 33 |

| Carabidae | Cymindis | Cymindis americana | 9 |

| Carabidae | Cymindis | Cymindis limbata | 203 |

| Carabidae | Cymindis | Cymindis platycollis | 8 |

| Carabidae | Dicaelus | Dicaelus ambiguus | 22 |

| Carabidae | Dicaelus | Dicaelus elongatus | 11 |

| Carabidae | Dicaelus | Dicaelus sculptilis | 78 |

| Carabidae | Dromius | Dromius piceus | 1 |

| Carabidae | Elaphropus | Elaphropus granarius | 1 |

| Carabidae | Galerita | Galerita bicolor | 19 |

| Carabidae | Galerita | Galerita janus | 2 |

| Carabidae | Harpalus | Harpalus faunus | 1 |

| Carabidae | Harpalus | Harpalus katiae | 1 |

| Carabidae | Harpalus | Harpalus pensylvanicus | 5 |

| Carabidae | Lebia | Lebia analis | 1 |

| Carabidae | Lebia | Lebia marginicollis | 1 |

| Carabidae | Lebia | Lebia viridis | 37 |

| Carabidae | Lophoglossus | Lophoglossus haldemanni | 1 |

| Carabidae | Mioptachys | Mioptachys flavicauda | 12 |

| Carabidae | Notiophilus | Notiophilus novemstriatus | 67 |

| Carabidae | Platynus | Platynus decentis | 9 |

| Carabidae | Platynus | Platynus parmarginatus | 2 |

| Carabidae | Plochionus | Plochionus timidus | 2 |

| Carabidae | Pterostichus | Pterostichus permundus | 105 |

| Carabidae | Pterostichus | Pterostichus punctiventris | 11 |

| Carabidae | Rhadine | Rhadine ozarkensis | 1 |

| Carabidae | Scaphinotus | Scaphinotus unicolor | 4 |

| Carabidae | Scaphinotus | Scaphinotus fissicollis | 12 |

| Carabidae | Scaphinotus | Scaphinotus infletus | 1 |

| Carabidae | Selenophorus | Selenophorus ellipticus | 4 |

| Carabidae | Selenophorus | Selenophorus gagatinus | 8 |

| Carabidae | Selenophorus | Selenophorus opalinus | 1 |

| Carabidae | Stenolophus | Stenolophus ochropezus | 5 |

| Carabidae | Synuchus | Synuchus impunctatus* | 3 |

| Carabidae | Tachyta | Tachyta parvicornis | 3 |

| Carabidae | Tachys | Tachys columbiensis | 4 |

| Carabidae | Tachys | Tachys oblitus | 2 |

| Carabidae | Trichotichnus | Trichotichnus autumnalis | 176 |

| Carabidae | Trichotichnus | Trichotichnus fulgens | 11 |

| Carabidae | Trichotichnus | Trichotichnus vulpeculus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Aegomorphus | Aegomorphus modestus | 8 |

| Cerambycidae | Aegormorphus | Aegormorphus quadrigibbus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Anelaphus | Anelaphus parallelus | 162 |

| Cerambycidae | Anelaphus | Anelaphus pumilus | 4 |

| Cerambycidae | Astyleiopus | Astyleiopus variegatus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Astylidius | Astylidius parvus | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Astylopsis | Astylopsis macula | 4 |

| Cerambycidae | Astylopsis | Astylopsis sexguttata | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Bellamira | Bellamira scalaris | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Brachyleptura | Brachyleptura champlaini | 5 |

| Cerambycidae | Callimoxys | Callimoxys sanguinicollis | 4 |

| Cerambycidae | Centrodera | Centrodera sublineata | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Clytoleptus | Clytoleptus albofasciatus | 6 |

| Cerambycidae | Cyrtinus | Cyrtinus pygmaeus | 5 |

| Cerambycidae | Cyrtophorus | Cyrtophorus verrucosus | 17 |

| Cerambycidae | Dorcaschema | Dorcaschema alternatum | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Dorcaschema | Dorcaschema cinereum | 15 |

| Cerambycidae | Dorcaschema | Dorcaschema nigrum | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Dorcaschema | Dorcaschema wildii | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Eburia | Eburia quadrigeminata | 7 |

| Cerambycidae | Ecyrus | Ecyrus dasycerus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Elytrimitatrix | Elytrimitatrix undata | 30 |

| Cerambycidae | Elaphidion | Elaphidion mucronatum | 196 |

| Cerambycidae | Enaphalodes | Enaphalodes rufulus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Euderces | Euderces reichei | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Euderces | Euderces picipes | 5 |

| Cerambycidae | Euderces | Euderces pini | 3 |

| Cerambycidae | Eupogonius | Eupogonius pauper | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Gaurotes | Gaurotes cyanipennis | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Graphisurus | Graphisurus despectus | 8 |

| Cerambycidae | Graphisurus | Graphisurus fasciatus | 10 |

| Cerambycidae | Heterachthes | Heterachthes quadrimaculatus | 18 |

| Cerambycidae | Hyperplatys | Hyperplatys maculata | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Knulliana | Knulliana cincta | 10 |

| Cerambycidae | Leptostylus | Leptostylus transversus | 18 |

| Cerambycidae | Lepturges | Lepturges angulatus | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Lepturges | Lepturges confluens | 9 |

| Cerambycidae | Micranoplium | Micranoplium unicolor | 3 |

| Cerambycidae | Molorchus | Molorchus bimaculatus | 65 |

| Cerambycidae | Monochamus | Monochamus titillator | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus acuminatus | 60 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus caprea | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus horridus | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus jouteli | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus mucronatus | 133 |

| Cerambycidae | Neoclytus | Neoclytus scutellaris | 129 |

| Cerambycidae | Necydalis | Necydalis mellita | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Oberea | Oberea ulmicola | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Obrium | Obrium maculatum | 10 |

| Cerambycidae | Oncideres | Oncideres cingulata | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Orthosoma | Orthosoma brunneum | 7 |

| Cerambycidae | Parelaphidion | Parelaphidion aspersum | 7 |

| Cerambycidae | Phymatodes | Phymatodes amoenus | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Phymatodes | Phymatodes testaceus | 8 |

| Cerambycidae | Phymatodes | Phymatodes varius | 4 |

| Cerambycidae | Physocnemum | Physocnemum brevilineum | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Prionus | Prionus imbricornis | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Purpuricenus | Purpuricenus humeralis | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Purpuricenus | Purpuricenus paraxillaris | 13 |

| Cerambycidae | Saperda | Saperda discoidea | 9 |

| Cerambycidae | Saperda | Saperda imitans | 29 |

| Cerambycidae | Saperda | Saperda lateralis | 9 |

| Cerambycidae | Saperda | Saperda tridentata | 3 |

| Cerambycidae | Sarosesthes | Sarosesthes fulminans | 5 |

| Cerambycidae | Stenelytrana | Stenelytrana emarginata | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Stenocorus | Stenocorus cinnamopterus | 7 |

| Cerambycidae | Stenosphenus | Stenosphenus notatus | 73 |

| Cerambycidae | Sternidius | Sternidius alpha | 6 |

| Cerambycidae | Strangalepta | Strangalepta abbreviata | 1 |

| Cerambycidae | Strangalia | Strangalia bicolor | 31 |

| Cerambycidae | Strangalia | Strangalia luteicornis | 205 |

| Cerambycidae | Strophiona | Strophiona nitens | 24 |

| Cerambycidae | Tilloclytus | Tilloclytus geminatus | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Trachysida | Trachysida mutabilis | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Trigonarthris | Trigonarthris minnesotana | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Trigonarthris | Trigonarthris proxima | 3 |

| Cerambycidae | Typocerus | Typocerus lugubris | 2 |

| Cerambycidae | Typocerus | Typocerus velutinus | 46 |

| Cerambycidae | Typocerus | Typocerus zebra | 5 |

| Cerambycidae | Urgleptes | Urgleptes querci | 28 |

| Cerambycidae | Urgleptes | Urgleptes signatus | 9 |

| Cerambycidae | Xylotrechus | Xylotrechus colonus | 360 |

| Curculionidae | Acalles | Acalles carinatus | 11 |

| Curculionidae | Acalles | Acalles clavatus* | 5 |

| Curculionidae | Acalles | Acalles minutissimus* | 5 |

| Curculionidae | Acoptus | Acoptus suturalis* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Anthonomus | Anthonomus juniperinus* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Anthonomus | Anthonomus nigrinus | 3 |

| Curculionidae | Anthonomus | Anthonomus rufipennis | 5 |

| Curculionidae | Anthonomus | Anthonomus suturalis | 22 |

| Curculionidae | Aphanommata | Aphanommata tenuis | 9 |

| Curculionidae | Apteromechus | Apteromechus ferratus | 600 |

| Curculionidae | Anametis | Anametis granulata* | 5 |

| Curculionidae | Auleutes | Auleutes nebulosus complex | 2 |

| Curculionidae | Buchananius | Buchananius sulcatus | 4 |

| Curculionidae | Canistes | Canistes schusteri | 26 |

| Curculionidae | Caulophilus | Caulophilus dubius | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Cercopeus | Cercopeus chrysorrhoeus | 560 |

| Curculionidae | Chalcodermus | Chalcodermus inaequicollis | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus affinis | 9 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus anaglypticus | 39 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus aratus | 162 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus carinifer | 56 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus elegans | 44 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus naso | 130 |

| Curculionidae | Conotrachelus | Conotrachelus posticatus | 979 |

| Curculionidae | Cophes | Cophes fallax | 73 |

| Curculionidae | Cophes | Cophes obtentus | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Cossonus | Cossonus impressifrons | 12 |

| Curculionidae | Craponius | Craponius inaequalis | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Cryptorhynchus | Cryptorhynchus fuscatus | 6 |

| Curculionidae | Cryptorhynchus | Cryptorhynchus tristis | 168 |

| Curculionidae | Curculio | Curculio othorhynchus | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Cyrtepistomus | Cyrtepistomus castaneus | 133 |

| Curculionidae | Dichoxenus | Dichoxenus setiger | 76 |

| Curculionidae | Dietzella | Dietzella zimmermanni | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Dryophthorus | Dryophthorus americanus | 30 |

| Curculionidae | Epacalles | Epacalles inflatus | 65 |

| Curculionidae | Eubulus | Eubulus bisignatus | 28 |

| Curculionidae | Eubulus | Eubulus obliquefasciatus | 193 |

| Curculionidae | Eudociminus | Eudociminus mannerheimii* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Eurhoptus | Eurhoptus sp. 1 | 28 |

| Curculionidae | Eurhoptus | Eurhoptus pyriformis | 15 |

| Curculionidae | Geraeus | Geraeus penicillus | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Hypera | Hypera compta | 4 |

| Curculionidae | Hypera | Hypera meles | 19 |

| Curculionidae | Hypera | Hypera nigrirostris | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Hypera | Hypera postica | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Idiostethus | Idiostethus subcalvus* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Laemosaccus | Laemosaccus nephele complex | 3 |

| Curculionidae | Leichrops | Lechriops oculatus | 30 |

| Curculionidae | Lymantes | Lymantes sandersoni | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Madarellus | Madarellus undulatus* | 9 |

| Curculionidae | Magdalis | Magdalis armicollis* | 3 |

| Curculionidae | Magdalis | Magdalis barbita* | 5 |

| Curculionidae | Mecinus | Mecinus pascuorum* | 2 |

| Curculionidae | Myrmex | Myrmex chevrolatii* | 7 |

| Curculionidae | Myrmex | Myrmex myrmex* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Nicentrus | Nicentrus lecontei* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Oopterinus | Oopterinus perforatus | 17 |

| Curculionidae | Otiorhynchus | Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus* | 46 |

| Curculionidae | Pandeletius | Pandeletius hilaris | 51 |

| Curculionidae | Piazorhinus | Piazorhinus pictus* | 2 |

| Curculionidae | Phyllotrox | Phyllotrox ferrugineus* | 20 |

| Curculionidae | Plocamus | Plocamus hispidulus* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Pseudobaris | Pseudobaris nigrina* | 9 |

| Curculionidae | Pseudopentarthrum | Pseudopentarthrum simplex* | 13 |

| Curculionidae | Rhinoncus | Rhinoncus pericarpius* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Sitona | Sitona lineatus* | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Stenoscelis | Stenoscelis brevis* | 4 |

| Curculionidae | Tachyerges | Tachyerges niger | 1 |

| Curculionidae | Tomolips | Tomolips quercicola* | 2 |

| Curculionidae | Tychius | Tychius prolixus | 7 |

| Curculionidae | Tyloderma | Tyloderma foveolatum | 1 |

Thirty one species (12%) collected during this study represent new Arkansas state records: (Buprestidae) Actenodes acornis, Agrilus cephalicus, Agrilus ohioensis, Agrilus paracelti, Taphrocerus nicolayi; (Carabidae) Agonum punctiforme, Synuchus impunctatus; (Curculionidae) Acalles clavatus, Acalles minutissimus, Acoptus suturalis, Anthonomus juniperinus, Anametis granulata, Eudociminus mannerheimii, Idiostethus subcalvus, Madarellus undulatus, Magdalis armicollis, Magdalis barbita, Mecinus pascuorum, Myrmex chevrolatii, Myrmex myrmex, Nicentrus lecontei, Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus, Piazorhinus pictus, Phyllotrox ferrugineus, Plocamus hispidulus, Pseudobaris nigrina, Pseudopentarthrum simplex, Rhinoncus pericarpius, Sitona lineatus, Stenoscelis brevis, Tomolips quericola.

Three endemic carabids – Cyclotrachelus parasodalis, Rhadine ozarkensis, Scaphinotus infletus – were also collected.

Notes on Select Species

Agrilus ohioensis (Buprestidae) has been recorded from many eastern states, but is rarely collected. Larvae have been reported from American hornbeam, Carpinus caroliniana Walter, (

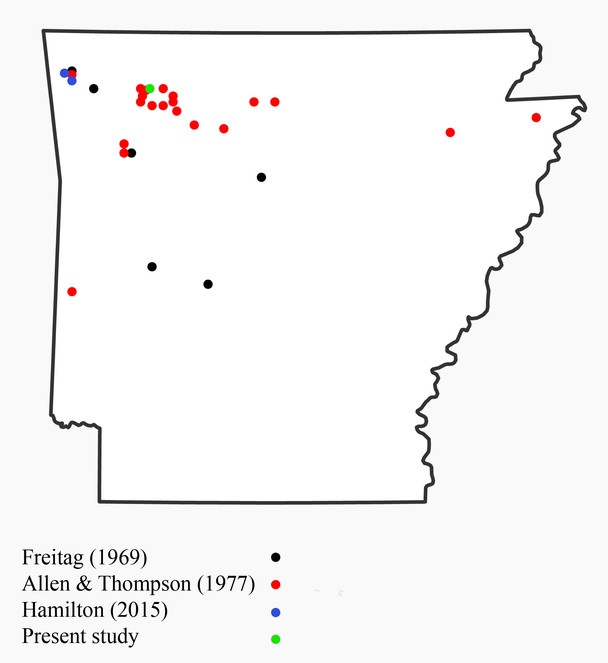

Agonum punctiforme (Carabidae) occurs from North Carolina to southeastern Texas, with a record from Missouri that "needs confirmed", and Amara cupreolata has been previously recorded in Arkansas but "the record needs confirmation" (

Cyclotrachelus parasodalis (Carabidae) is an Arkansas endemic which has only been reported in the literature a handful of times, including the original description and description of the larvae (

Rhadine ozarkensis (Carabidae) is previously known only from the type series collected in Fincher’s Cave, near Black Oak, Arkansas (Washington County, not Craighead County) (

Pterostichus punctiventris (Carabidae) ranges from northern Georgia south to Alabama west to east-central Missouri, eastern Oklahoma, and Texas (

Scaphinotus infletus (Carabidae) is known from only three specimens collected from three localities within 30 km of the study site (

Synuchus impunctatus (Carabidae) is known from Missouri and Kansas, but has not previously been recorded from Arkansas (

Tachys columbiensis (Carabidae) was thought to be confined to the Coastal Plain and Piedmont Plateau, ranging from southeastern Pennsylvania to southern Florida west to Mississippi and eastern Texas, though it has also been recorded from central Arkansas (Pulaski and Garland Counties) (

Trichotichnus vulpeculus (Carabidae) is recorded from western New Brunswick south to eastern Georgia, west to Wisconsin and northern Arkansas (

Acalles clavatus (Curculionidae) was previously known from Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana (

Acoptus suturalis (Curculionidae) is known from northeastern North America, from Quebec south to North Carolina and Illinois and Iowa; addition records are known from Georgia and Mexico (

Anametis granulata (Curculionidae) is found in northern and eastern North America, from Newfoundland and Quebec, south to New Jersey, west to Missouri, Wyoming and Montana; additional specimens are known from Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico (

Anthonomus juniperinus (Curculionidae) is known from the eastern United States, from Massachusetts south to Florida, west to West Virginia, as well as Texas, Oregon, and Paget, Bermuda (

Buchananius sulcatus (Curculionidae) is widely distributed in the eastern and southeastern United States (

Caulophilus dubius (Curculionidae) is known from Quebec and New York south to Georgia, west to Illinois and and Mississippi, as well as Texas (

Eubulus bisignatus (Curculionidae) is widespread in eastern and southern North America, ranging from Ontario south to Florida, west to Nebraska, Texas, Arizona, and California; it is also recorded from Mexico and Guatamala. It was not recorded from Arkansas by

Eubulus obliquefasciatus (Curculionidae) is commonly collected in flight-intercept traps and at lights. Adults have been collected on dead oak and sweetgum; otherwise, nothing is known about their biology (

The Eudociminus mannerheimii (Curculionidae) specimen collected during this study was included with other specimens collected near the field site in a forthcoming publication (Skvarla et al. in press) that suggests eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana L.) as a possible host as it is the only species of Cupressaceae present at the site. Additionally, the specimens represented a new state record and northwestern range expansion from previous records.

Idiostethus subcalvus (Curculionidae) is found from Pennsylvania south to South Carolina, west to Illinois and Missouri (

Madarellus undulatus (Curculionidae) is found in eastern North America, from Quebec and Connecticut south to Florida, west to South Dakota, Kansas, and Missouri (

Magdalis armicollis (Curculionidae) is found in the eastern United States from Connecticut south to Georgia, west to North Dakota, Montana, Nebraska, and Texas (

Magdalis barbita (Curculionidae) is found in North Ameica from Conneticut and Ontario south to Georgia, west to Montana, Texas, Nevada, and California (

Myrmex myrmex (Curculionidae) is native to the eastern United States, from Conneticut south to Florida, west to Indiana and Iowa (

Notiodes limatulus (Curculionidae) is widespread in North Ameica, ranging from New York south to Georgia, west to Idaho, Texas, and California, and into Mexico. It was not recorded in Arkansas by

Otiorhynchus rugosostriatus (Curculionidae) is adventive from Europe and has been established in North America since 1876; it is now widespread through the United States and Canada (

Rhinoncus pericarpius (Curculionidae) is adventive from the Palaerctic (

Stenoscelis brevis (Curculionidae) is widespread is eastern North America, from Ontario and Quebec south to Florida, west to Wisconsin, Kansas, and Mississippi (

Tachyerges niger (Curculionidae) was not reported from Arkansas by

Tychius picirostris (Curculionidae) is adventive from Europe and widely established in North America (

Discussion

It is unsurprising that few Carabidae represented new state records as carabid workers formerly associated with the University of Arkansas (e.g., R. T. Allen, C. E. Carlton, R. G. Thompson) have thoroughly surveyed the region. Conversely, nearly one in five Buprestidae (19%) and one in three Curculionidae (32%) collected during this study represent new state records. Such high percentages of unrecorded species in charismatic and diverse taxa highlights how little attention many groups have received in the state and how much basic science and natural history is left to be done in 'The Natural State'.

Buprestids are capable of flying between habitat patches and rapidly colonizing new areas, so it is unlikely that new species will be discovered even though buprestids are understudied in the Interior Highlands. However, considering the high number of endemic species that are restricted to leaf litter habitats or are poor dispersers, how relatively understudied leaf litter weevils are, and that known but undescribed species were collected during this study, it is likely that the Interior Highlands is a fruitful area for finding new and disjunct weevil species.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Messer for confirming the identity of Rhadine ozarkensis and other carabids; Robert Anderson for confirming the identity of Eurhoptus species; Ted MacRae for confirming new buprestid state records; and Hailey Higgins for curating and identifying cerambycid specimens. This project and the preparation of this publication was funded in part by the State Wildlife Grants Program (Grant # T39-05) of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through an agreement with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

Author contributions

Michael Skvarla performed all responsibilities associated with collecting the specimens, including trap maintenance and sample collection; sorted samples; identified all the majority of non-buprestid specimens; and prepared the manuscript. Danielle Fisher sorted samples, coarse-sorted specimens to higher taxa (family/genus), and identified some specimens to species. Kyle Schnepp identified the Buprestidae and commented on the manuscript prior to submission. Ashley Dowling supervised the lab in which M. Skvarla and D. Fisher performed the work, provided financial support by securing funding, and commented on the manuscript prior to submission.

References

- Cottus specus, a new troglomorphis species of sculpin (Cottidae) from southeastern Missouri.Zootaxa3609(5):484‑494. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3609.5.4

- Insect endemism in the Interior Highlands of North America.Florida Entomologist73(4):539‑569. https://doi.org/10.2307/3495270

- Two new Scaphinotus from Arkansas with notes on other Arkansas species (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cychrini).Journal of the New York Entomological Society96(2):129‑139.

- Faunal composition and seasonal activity of Carabidae (Insecta: Coleoptera) in three different woodland communities in Arkansas.Annals of the Entomological Society of America70(1):31‑34. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/70.1.31

- Arkansas Wildlife Action Plan.Arkansas Game and Fish Commission,Little Rock, Arkansas,2028pp. URL: http://www.wildlifearkansas.com/strategy.html

- A Review of the Genus Eubulus Kirsch 1869 in the United States and Canada (Curculionidae: Cryptorhynchinae).The Coleopterists Bulletin62(2):287‑296. https://doi.org/10.1649/1064.1

- Anderson RS (2002) Curculionidae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC, Skelley PE, Franks JH (Eds) American Beetles, volume 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea.CRC Press,New York, New York,861pp.

- Tychius meliloti Stephens new to Canada with a brief review of the species of Tychius Germar introduced into North America (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Canadian Entomologist126:1363‑1368. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent1261363-6

- Anderson RS, Kissinger DG (2002) Brentidae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC, Skelley PE, Franks JH (Eds) American Beetles, volume 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea.CRC Press,New York, New York,861pp.

- Ozarks Plateaus. http://www.geology.ar.gov/education/ozark_plateaus.htm. Accessed on: 2015-9-07.

- Arnett RH, Ivie MA (2001) Rhysodidae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC (Eds) American Beetles. Volume 1. Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia.CRC Press,New York, New York,433pp. [ISBN0-8493-1925-0].

- Fishes of South Dakota.University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Miscellaneous Publications119:1‑132.

- Type of wood preferred by Coleoptera found in decadent parts of living elm trees.Journal of Economic Entomology34(3):475‑476. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/34.3.475a

- A taxonomic study of the North American Licinini with notes on the Old World species of the genus Diplocheila Brullé (Coleoptera).Memoirs of the American Entomological Society16:1‑258.

- The subgenera of Clivina Latreille in the Western Hemisphere, and a revision of subgenus Antroforceps Barr (new status), with notes about evolutionary aspects (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Clivinini).Coleopterological Society of Osaka1:129‑156.

- The taxonomy and speciation of Pseudophonus.The Catholic University of America Press,Washington, D.C.,94pp.

- Ball GE, Bousquet Y (2001) Carabidae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC (Eds) American Beetles. Volume 1. Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia.CRC Press,New York, New York,443pp.

- The taxonomy of the Nearctic species of the genus Calathus.Transactions of the American Entomological Society98:412‑433.

- Synopsis of the species of subgenus Progaleritina Jeannel, including reconstructed phylogeny and geographical history (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Galerita Fabricius).Transactions of the American Entomological Society109(4):295‑356.

- The cavernicolous beetles of the subgenus Rhadine, genus Agonum (Coleoptera: Carabidae).American Midland Naturalist64:45‑65. https://doi.org/10.2307/2422893

- Revision of Rhadine LeConte (Coleoptera, Carabidae) I. The subterranea Group.American Museum Novitates2539:1‑30. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/2246/5413

- Micarea micrococca and M. prasina, the first assessment of two very similar species in eastern North America.The Bryologist117(3):223‑231. https://doi.org/10.1639/0007-2745-117.3.223

- Endemism in rock outcrop plant communities of unglaciated eastern United States: an evaluation of the roles of edaphic, genetic and light factors.Journal of Biogeography15:829‑840. https://doi.org/10.2307/2845343

- Vegetation of limestone and dolomite glades in the Ozarks and Midwest Regions of the United States.Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden87(2):286‑294. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666165

- Mayflies (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) of the Kiamichi River Watershed, Oklahoma.Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society72(3):297‑305.

- A revision of the genus Chlaenius Bonelli (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in North America.Miscellaneous Publications of the Entomological Society of America1:97‑166.

- Rhysodini. Wrinkled bark beetles. http://tolweb.org/Rhysodini. Accessed on: 2014-1-03.

- Two new taxa of Clindium (Coleoptera: Rhysodidae or Carabidae) from the Eastern U.S., with a revised key to Clindium.The Coleopterists Bulletin29(2):65‑68.

- Recovering cryptic diversity and ancient drainage patterns in eastern North America: Historical biogeography of the Notropis rubellus species group (Teleostei: Cypriniformes).Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution46(2):721‑737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2007.07.008

- Checklist of the Oxypeltidae, Vesperidae, Disteniidae and Cerambycidae, (Coleoptera) of the Western Hemisphere. http://www.zin.ru/animalia/coleoptera/pdf/checklist_cerambycoidea_2013.pdf. Accessed on: 2015-9-11.

- Blair WF (1965) Amphibian speciation. In: Wright HE, Frey DG (Eds) The Quaternary of the United States.Princeton University Press,Princeton, New Jersey.

- Rhynchophora or weevils of north eastern America.The Nature Publishing Company,Indianapolis, Indiana,682pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.1557

- Old traps for new weevils: New records for curculionids (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), brentids (Coleoptera: Brentidae) and anthribids (Coleoptera: Anthribidae) from Jefferson Co., Florida.Florida Entomologist85(4):632‑644. https://doi.org/10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0632:otfnwn]2.0.co;2

- Taxonomy and biology of Endalus Laporte and Onychylis LeConte in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Texas A&M University,College Station, Texas,302pp.

- Pressurized-canister trunk injection of acephate, and changes in abundance of red elm bark weevil (Magdalis armicollis) on American elm (Ulmus americana).Arboriculture & Urban Forestry35(3):148‑151.

- Weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) diversity and abundance in two Quebec vineyards.Annals of the Entomological Society of America98(4):565‑574. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0565:WCCDAA]2.0.CO;2

- Descriptions of new or poorly known species of Gastroticta Casey, 1918 and Paraferonina Ball, 1965 (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Pterostichus Bonelli, 1810).Journal of the New York Entomological Society100(3):510‑521.

- Rediscovery of Clivina morio Dejean with the description of Leucocara, a new subgenus of Clivina Latreille (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Clivinini).ZooKeya25:37‑48. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.25.276

- Description of a new species of Platynus Bonelli from the Appalachian Mountains of eastern North America (Coleoptera, Carabidae).ZooKeys163:69‑81. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.163.2295

- Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera: Adephaga) of America, north of Mexico.ZooKeys245:1‑1722. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.245.3416

- Redescription of Stenolophus thoracicus Casey (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Harpalini), a valid species.ZooKeys53:25‑31. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.53.470

- Caddisflies (Insecta: Trichoptera) of mountainous regions in Arkansas, with new state records for the order.Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society62(2):234‑244.

- Geomorphic history of the Ozarks of Missouri.41.Geological Survey and Water Resources,Rolla, Missouri,174pp.

- The Insects and Arachnids of Canada, part 21. The Weevils of Canada and Alaska: Volume 1. Coleoptera: Curculionoidea, excluding Scolytidae and Curculionidae.Agriculture Canada,Ottawa, Ontario,217pp.

- The Insects and Arachnids of Canada Series, Part 25. Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Entiminae.NRC Research Press,Ottawa, Ontario,327pp.

- Observations on the Bionomics of Myrmex laevicollis (Horn) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society48(2):160‑169.

- Two new species of Elymus (Poaceae) in the southern U.S.A. and other notes on North American Elymus species.SIDA22(1):485‑494.

- A new species of Arianops from Central Arkansas and biogeographic implications of the Interior Highlands Arianops species (Coleoptera: Pselaphidae).The Coleopterists Bulletin44(3):365‑371.

- Diversity of litter-dwelling beetles in the Ouachita Highlands of Arkansas, USA (Insecta: Coleoptera).Biodiversity and Conservation7:1589‑1605. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008840427909

- Illustrated revision of the Cerambycidae of North America. I. Subfamilies Parandrinae, Spondylidinae, Aseminae, Prioninae.Wolfsgarden Books,Burbank, California,150pp. [ISBN1-885850-02-6]

- Illustrated Revision of the Cerambycidae of North America. Vol. II. Lepturinae.Wolfsgarden Books,Burbank, California,446pp.

- Checklist of Cerambycidae. The Longhorned Beetles. Checklist of the Cerambycidae and Disteniidae of North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Coleoptera).Plexus Publishing,Medford, New Jersey,138pp.

- Ground beetles and wrinkled bark beetles of South Carolina (Coleoptera: Geadephaga: Carabidae and Rhysodidae). Biota of South Carolina, Volume 1.Clemson University Public Service Publishing,Clemson, South Carolina,149pp.

- Weevils of South Carolina (Coleoptera: Nemonychidae, Attelabidae, Brentidae, Ithyceridae, and Curculionidae). Biota of South Carolina, Volume 6.Clemson University Public Service Publishing,Clemson, South Carolina,276pp.

- A taxonomic revision of the weevil genus Tychius Germar in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series13(3):1‑39.

- The Anthonomus juniperinus group, with descriptions of two new species (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Insecta Mundi119:1‑10.

- Ecological regions of North America: Toward a common perspective.Comission for Environmental Coopteration,Montreal, Québec,71pp.

- The Mississippi Embayment, North America: a first order continental structure generated by the Cretaceous superplume mantle event.Journal of Geodynamics34:163‑176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-3707(02)00019-4

- Conservation phylogenetics of Ozark crayfishes: Assigning priorities for aquatic habitat protection.Biological Conservation84:107‑117. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3207(97)00112-2

- Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode. Accessed on: 2015-9-12.

- Obligate Cave Fauna of the 48 Contiguous United States.Conservation Biology14(2):386‑401. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99026.x

- Geology and geochemistry of the Precambrian rocks in the Central Interior Region of the United States.Geological Survey Professional Paper1241-C:1‑20. URL: http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1241C

- Phylogenetic estimation of species limits in dwarf crayfishes from the Ozarks: Orconectes macrus and Orconectes nana (Decapoda: Cambaridae).Southeastern Naturalist9(3):185‑198. https://doi.org/10.1656/058.009.s309

- New Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) records for Canada.ZooKeys309:13‑48. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.309.4667

- Geographic relations of Ozarkian amphibians and reptiles.Southwestern Naturalist4:174‑189. https://doi.org/10.2307/3668989

- Records of Indiana Coleoptera, II.Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science68:155‑158.

- Ecoregions of North America. http://www.epa.gov/wed/pages/ecoregions/na_eco.htm#Downloads. Accessed on: 2015-9-11.

- Neoperla (Plecoptera: Perlidae) of the southern Ozark and Ouachita Mountain Region, and two new species of Neoperla.Annals of the Entomological Society of America79(4):645‑661. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/79.4.645

- Studies of the subtribe Tachyina (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Bembidiini), Part III: Systematics, phylogeny, and zoogeography of the genus Tachyta Kirby.Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology208:1‑68. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.208

- A reclassification of bombardier beetles and a taxonomic revision of the North and Middle American species (Carabidae: Brachinida).Questiones Entomologicae6:4‑215.

- New Trichoptera records from Arkansas and Missouri.Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington112(4):483‑489. https://doi.org/10.4289/0013-8797.112.4.483

- The Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera of Missouri state parks, with notes on biomonitoring, mesohabitat sssociations, and distribution.Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society80(2):105‑129. https://doi.org/10.2317/0022-8567(2007)80[105:TEPATO]2.0.CO;2

- The beetle community of small oak twigs in Louisiana, with a literature review of Coleoptera from fine woody debris.Coleopterists Bulletin63(239):263. https://doi.org/10.1649/1141.1

- Comparison of Coleoptera emergent from various decay classes of downed coarse woody debris in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA.Insecta Mundi260:1‑80.

- Flawn PT (1968) Introduction. In: Flawn PT, Foldstein AJ, King PB, Weaver CE (Eds) The Ouachita System.2.The University of Texas,Austin, Texas,401pp.

- A new narrowly endemic speices of Dirca (Thymelaeaceae) from Kansas and Arkansas, with a phylogenetic overview and taxonomic synopsis of the genus.Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas3(2):485‑499.

- Arkansas Valley. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=441. Accessed on: 2015-9-10.

- Ozark Mountains. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=440. Accessed on: 2015-9-07.

- A description of the sections and subsections of the Interior Highlands of Arkansas and Oklahoma.Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science52:53‑62.

- A revision of the species of the genus Evarthrus LeConte (Coleoptera: Carabidae).Quaestiones Entomologicae5:88‑211.

- Monograph of the genus Curculio in the New World (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Part I. United States and Canada.Miscellaneous Publications of the Entomological Society of America6(5):239‑285.

- Revision of ground beetles of American genus Cychrus and four subgenera of genus Scaphinotus (Coleoptera, Carabidae).Bulletin of hte American Museum of Natural History152(2):51‑102.

- The potential of Magdalis spp. in the transmission of Ceratocystis ulmi (Buis.) Moreau.Journal of Economic Entomology56(2):238‑239. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/56.2.238

- Subterranean biodiversity of Arkansas, Part I: Bioinventory and bioassessment of caves in the Sylamore Ranger District, Ozark National Forest, Arkansas.Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science57:44‑58.

- Range extension and status update for the Oklahoma cave crayfish, Cambarus tartarus (Decapoda: Cambaridae).The Southwestern Naturalist51(1):94‑126. https://doi.org/10.1894/0038-4909(2006)51[94:REASUF]2.0.CO;2

- Floral host plants of adult beetles in Central Illinois: An historical perspective.Annals of the Entomological Society of America105(2):287‑297. https://doi.org/10.1603/an11120

- Boston Mountains. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=2389. Accessed on: 2015-9-09.

- Haldeman SS (1852) Appendix C. - Insects. In: Stransbury H (Ed.) Exploration and survey of the valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah, including a reconnaissance of a new route through the Rocky Mountains.Lippincott, Grambo, & Co.,Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,487pp.

- Potential beetle vectors of Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum on butternut.Plant Disease86(5):521‑527. https://doi.org/10.1094/pdis.2002.86.5.521

- The correlation between seasonality and diversity of arthropod communities in leaf litter.University of Arkansas,Fayetteville, Arkansas,94pp.

- The genus Pselaphorhynchites (Coleoptera: Rhynchitidae) in America North of Mexico.Annals of the Entomological Society of America64(5):982‑996. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/64.5.982

- A revision of the weevil genus Eugnamptus Schoenherr (Coleoptera: Rhynchitidae) in America north of Mexico.Transactions of the American Entomological Society115(4):475‑502.

- Hamilton RW (2002) Attelabidae. In: Arnett RH, Thamos MC, Skelley PE, Franks JH (Eds) American Beetles, volume 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea.CRC Press,New York, New York,861pp.

- On the insects injurious to hemp, especially Rhinoncus pericarpius, L.Insect World34:118‑123.

- The lichen genus Chrysothrix in the Ozark Ecoregion, including a preliminary treatment for eastern and central North America.Opuscula Philolichenum5:29‑42.

- The Fellhanera silicis group in eastern North America.Opuscula Philolichenum6:157‑174.

- Shortleaf pine-bluestem restoration in the Ouachita National Forest.Renewal & Recovery: Renewal of the shortleaf pine-bluestem grass ecosystem. Recovery of the red-cockaded woodpeckers1:1‑6. URL: http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5261917.pdf

- Heikens AL (1999) Savanna, barrens, and glade communities of the Ozark Plateaus Province. In: Anderson RC, Fralish JS, Baskin JM (Eds) Savannas, barrens, and rock outcrop plant communities of North America.Cambridge University Press,Cambridge, Massachusetts,470pp. [ISBN0-521-57322-X].

- Ozark Wildflowers.University of Georgia Press,Athens, Georgia,256pp. [ISBN9780820323374]

- Hespenheide HA (2002) Conoderinae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC, Skelley PE, Franks JH (Eds) American Beetles, volume 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea.CRC Press,New York, New York,861pp.

- New Lechriops species for the United States (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Conoderinae).Coleopterists Bulletin57(3):345‑352. https://doi.org/10.1649/580

- Petit Jean Mountain. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=6317. Accessed on: 2015-9-10.

- A new species of Bembidion Latrielle 1802 from the Ozarks, with a review of the North American species of subgenus Trichoplataphus Netolitzky 1914 (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Bembidiini).ZooKeys147:261‑275. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.147.1872

- New records Of Rhinoncus bruchoides (Herbst) for the Western Hemisphere and a revised key to the North American species of the genus Rhinoncus.Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington82:556‑561.

- Annotated list of elm insects in the United States.U.S. Department of Agriculture,Washington, D.C.,20pp.

- Bactrurus speleopolis, a new species of subterranean amphipod crustacean (Crangonyctidae) from caves in northern Arkansas.Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington119(1):15. https://doi.org/10.2988/0006-324x(2006)119[15:bsanso]2.0.co;2

- A revision of the species of Pandeletius Schonherr and Pandeleteinus Champion of America north of Mexico (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Proceedings of the California Academy of Science29(10):361‑421.

- A taxonomic revision of the Cymindis (Pinacodera) limbata species group (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Lebiini), including description of a new species from Florida, U.S.A.ZooKeys259:1‑73. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.259.2970

- Genus Ormiscus. http://bugguide.net/node/view/257929. Accessed on: 2015-8-20.

- The attractiveness of manuka oil and ethanol, alone and in combination, to Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and other Curculionidae.Florida Entomologist97(2):861‑864. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.097.0281

- Cottus immaculatus, a new species of sculpin (Cottidae) from the Ozark Highlands of Arkansas and Missouri, USA.Zootaxa2340:50‑64.

- A new name for Zaglyptus LeConte, 1876 (not Forster, 1868) and a rewview of the North American species (Curculionidae, Baridinae).Coleopterists Bulletin11:47‑51.

- Two new species of Lecanora with gyrophoric acid from North America.Opuscula Philolichenum7:21‑28.

- Dynamics and spatial pattern of a virgin old-growth hardwood pine forest in the Ouachita Mountains, Oklahoma, from 1896 to 1994.Oklahoma State University,Stillwater, Oklahoma,141pp.

- Notiophilus palustris (Coleoptera, Carabidae), a Eurasian carabid beetle new to North America.Entomological News101:211‑212.

- Xeric limestone prairies of Eastern United States.University of Kentucky,Lexington, Kentucky,223pp. URL: http://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1272&context=gradschool_diss

- Lepraria normandinoides, a new widespread species from Eastern North America.Opuscula Philolichenum4:45‑50.

- Studies in lichens and lichenicolous fungi – No. 19: Further notes on species from the Coastal Plain of southeastern North America.Opuscula Philolichenum13:155‑176.

- Identification of New World Agonum, review of the Mexican fauna, and description of Incagonum, new genus, from South America (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Platynini).Journal of the New York Entomological Society102(1):1‑55.

- New North American Platynus Bonelli (Coleoptera: Carabidae), a key to species north of Mexico, and notes on species from the southwestern United States.Coleopterists Bulletin50:301‑320.

- The ground beetles (Carabidae, excl. Cicindelinae) of Canada and Alaska.Berlingska Boktryckeriet,Lund, Sweden,1192pp.

- Illustrated Key to the Longhorned Woodboring Beetles of the Eastern United States. Special Publication No. 3.The Coleopterists Society,North Potomac, Maryland,206pp.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part III: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Cerambycinae, tribes Opsimini through Megaderini.University of California Publications in Entomology20:1‑188.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part II: Taxonomy and classification of the Parandrinae, Prioninae, Spondylinae, and Aseminae.University of California Publications in Entomology19:1‑102.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part IV: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Cerambycinae, tribes Elaphidionini through Rhinotragini.University of California Publications in Entomology21:1‑165.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part V: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Cerambycinae, tribes Callichromini through Ancylocerini.University of California Publications in Entomology22:1‑197.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part VI, No. 1: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Lepturinae.University of California Publications in Entomology69:1‑138.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part VI, No.2: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Lepturinae.Univeristy of California Publications in Entomology80:1‑186.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part VII, No. 1: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Lamiinae, tribes Parmenini through Acanthoderini.University of California Publications in Entomology102:1‑258.

- The Cerambycidae of North America. Part VII, No. 2: Taxonomy and classification of the subfamily Lamiinae, tribes Acanthocinini through Hemilophini.University of California Publications in Entomology114:1‑292.

- Glossary of Weevil Characters. International Weevil Community Website. http://weevil.info/glossary-weevil-characters. Accessed on: 2014-1-12.

- Review of the genus Purpuricenus Dejean (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in North America.Pan-Pacific Entomologist76(3):137‑169.

- A revision of the genus Lebia Latreille in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera, Carabidae).Quaestiones Entomologicae3:139‑242.

- The weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) of the Maritime Provinces of Canada, II: New records from Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island and regional zoogeography.Canadian Entomologist139:397‑442. https://doi.org/10.4039/n06-021

- Masters RE, Skeen JE, Whitehead J (1995) Preliminary fire history of McCurtain County Wilderness Area and implications for Red-cockaded Woodpecker management. In: Kulhavy DL, Hooper RG, Costa R (Eds) Red-cockaded Woodpecker: Recovery, ecology and management.Center for Applied Studies, College of Forestry, Stephan F. Austin State University,Nacogdoches, Texas,551pp. [ISBN0938361120].

- A preliminary survey of the Trichoptera of the Ozark Mountains, Missouri, USA.Entomological News103:19‑29.

- Immigrant phytophagous insects on woody plants in the United States and Canada: An annotated list.North Central Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture,St. Paul, Minnesota,30pp.

- The Ephemeroptera of mountainous Arkansas.Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society51(3):360‑379.

- Karst, Springs, Losing Streams and Caves in Missouri. http://dnr.mo.gov/env/wrc/springsandcaves.htm. Accessed on: 2015-9-07.

- Sedimentary and tectonic history of the Ouachita Mountains.Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publication22:120‑142. https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.74.22.0120

- Caddisflies (Trichoptera) of the Interior Highlands of North America.Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute56:1‑313.

- Cave/Karst Systems. http://www.nps.gov/ozar/learn/nature/cave.htm. Accessed on: 2015-9-07.

- Systematics and ecology of Gastrocopta (Gastrocopta) rogersensis (Gastropoda: Pupillidae), a new species of land snail from the Midwest of the United States of America.The Nautilus115(3):10‑114.

- Additional notes on the biology and distribution of Buprestidae (Coleoptera) in North America, part III.Coleopterists Bulletin44(3):349‑354.

- Additional notes on the biology and distribution of Buprestidae (Coleoptera) of North America.Coleopterists Bulletin35(2):129‑151.

- A catalog and bibliography of the Buprestoidea of America North of Mexico.The Coleopterists Society,274pp.

- A new hedge-nettle (Stachys: Lamiaceae) from the Interior Highlands of the United States, and keys to the southeastern species.Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas2(2):761‑769.

- The anisodactylines (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae: Harpalini): Classification, evolution and zoogeography.Quaestiones Entomologicase9(4):266‑480.

- Classification, cladistics, and natural history of native North American Harpalus Latreille (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae: Harpalini), excluding the subgenera Glanodes and Pseudophonus. Thomas Say Foundation Monographs No. 13.Entomological Society of America,Lanham, Maryland,310pp.

- A method for trapping Hylobius abietis (L.) with a standardized bait and its potential for forecasting seedling damage.Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research2:199‑213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827588709382458

- Revision of the “Rice Water Weevil” genus Lissorhoptrus LeConte (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in North America North of Mexico.Coleopterists Bulletin68(2):163‑186. https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065x-68.2.163

- A new Oopterinus from Arkansas (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).Entomological News96:101‑104.

- A catalog of the Coleoptera of America north of Mexico. Family: Curculionidae, subfamilies: Acicnemidinae, Cossoninae, Rhytirrhininae, Molytinae, Petalochilinae, Trypetidinae, Dryophthorinae, Tachygoninae, Thecesterninae.Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture,Washington D.C.,48pp.

- A catalog of the Coleoptera of America north of Mexico. Family: Curculionidae, subfamily Erirhininae.Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture,Washington, D.C.,40pp.

- Annotated checklist of the weevils (Curculionidae sensu lato) of North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea).American Entomological Institute,Ann Arbor, Michigan,382pp.

- Weevils of the genus Cercopeus Schoenherr from South Carolina, USA (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Entiminae.Insecta Mundi121:1‑29.

- Distribución e incidencia poblacional del picudo de la yema del manzano Anametis granulatus Say (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), en la Sie rra de Arteaga, Coahuila. [Population distribution and incidence of apple bud weevil Anametis granulatus Say (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Sierra de Arteaga, Coahuila].Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro,Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico,52pp. [InSpanish].

- Field Guide to the Jewel Beetles (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) of Northeastern North America.Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Canadian Food Inspection Agency),411pp.

- First troglobitic weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in North America? Description of a new eyeless species of Lymantes Schoenherr from Central Texas caves.Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs. Studies on the cave and endogean fauna of North America7(5):115‑123.

- http://peakery.com/. Accessed on: 2015-9-10.

- A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada. Identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae.Oxford University Press,New York, New York,227pp.

- New and noteworthy additions to the Arkansas fern flora.Phytoneuron30:1‑33.

- Poole FG, Perry WJ, Madrid RJ, Amaya-Martínz R (2005) Tectonic synthesis of the Ouachita-Marathon-Sonora orogenic margin of southern Laurentia: Stratigraphic and structural implications for timing and deformational events and plate-tectonic model. In: Anderson TH, Nourse JA, McKee JE, Steiner MB (Eds) The Mojave-Sonora megashear hypothesis: Development, assessment, and alternatives.Geological Society of America,692pp. https://doi.org/10.1130/2005.2393(21)

- The stoneflies of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains (Plecoptera).Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute38:1‑116.

- A Review of the species of Geraeus Pascoe and Linogeraeus Casey found in the continental United States (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Baridinae).Coleopterists Bulletin63(2):123‑172. https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065x-63.2.123

- Buchananius sulcatus (Leconte) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Baridinae) Reared from the Fruiting Bodies of the Ascomycete Fungus Trichoderma peltatum (Berk.) Samuels, Jaklitsch, and Voglmayr in Maryland, USA.Coleopterists Bulletin68:399‑402. https://doi.org/10.1649/072.068.0310

- A new species of Sabatia (Gentianaceae) from Saline County, Arkansas.SIDA21(3):1249‑1262.

- Abundance and distribution of potential arthropod prey species in a typical Golden cheeked Warbler habitat.Texas A&M University,College Station, Texas,182pp.

- Kongsbergia robisoni, n. sp. (Araci: Hydrachnidiae: Aturidae) from the Interior Highlands of North America based on morphologuy and molecular genetic analysis.International Journal of Acarology37:194‑205. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2010.548404

- Bryogeography of the Interior Highlands of North America: Taxa of critical importance.The Bryologist89(1):32‑34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3243074

- Range and ecology of Helenium virginicum in the Missouri Ozarks.Southeastern Naturalist5(3):515‑522. https://doi.org/10.1656/1528-7092(2006)5[515:RAEOHV]2.0.CO;2

- Flowers and insects: lists of visitors of four hundred and fifty three flowers.The Science Press Printing Company,Lancaster, Pennsylvania,221pp.

- The Arkansas endemic biota: An update with additions and deletions.Journal of the Arkansas Academic of Science62:84‑96.

- Only in Arkansas: A study of the endemic plants and animals of the state.University of Arkansas Press,Fayetteville, Arkansas,121pp. [ISBN1-55728-326-5]

- Ross HH (1965) Pleistocene events and insects. In: Wright HE, Frey DG (Eds) The Quaternary of the United States.Princeton University Press,Princeton, New Jersey.

- The taxonomy of the Carex bicknellii Group (Cyperaceae) and new species for Central North America.Novon11(2):205‑228. https://doi.org/10.2307/3393060

- A systematic study of the genus Abacidus (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Pterostichini).The University of Arkansas,Fayetteville, Arkansas,48pp.

- Survey of Missouri mayflies with the first description of adults of Stenonema bednariki (Ephemeroptera: Heptageniidae).Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society70(2):132‑140.

- Surface stream occurrence and updated distribution of Allocrangonyx hubrichti Holsinger (Amphipoda: Allocrangonyctidae), and endemic subterranean amphipod of the Interior Highlands.Journal of Freshwater Ecology19(2):165‑168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2004.9664528

- New Rhyncophora. II.Journal of the New York Entomological Society15(2):75‑80.

- A new species of Astylopsis Casey (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Acanthocinini) from the Southeastern United States.Coleopterists Bulletin54(4):533‑539. https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065x(2000)054[0533:ansoac]2.0.co;2

- A distinctive new subspecies of Saperda lateralis F. (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from the Southeastern United States.Coleopterists Bulletin64(4):329‑336. URL: 10.1649/0010-065x-64.4.329

- The genus Conotrachelus Dejean (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) in the north central United States.University of Illinois Press,Urbana, Illinois,170pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.50123

- Selander RK (1965) Avian speciation in the Quaternary. In: Wright HE, Frey DG (Eds) The Quaternary of the United States.Princeton University Press,Princeton, New Jersey.

- ITS sequence evidence for the disjunct distribution between Virginia and Missouri of the narrow endemic Helenium virginicum (Asteraceae).Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society127(4):316‑323. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088650

- Pitfalls and preservatives: A review.Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario145:15‑43.

- The genus Dichoxenus Horn (Coleoptera, Curculionidae): 15. A contribution to knowledge of the Curculionidae.The Ohio Journal of Science56(3):165‑169.

- On Lymantes Schoenheer (Coleoptera, Curculionidae).Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences64:144‑152.

- Sawmill, the story of the cutting of the last great virgin forest east of the Rockies.The University of Arkansas Press,Fayetteville, Arkansas,246pp.

- Smith PW (1965) Recent adjustments in animal ranges. In: Wright HE, Frey DG (Eds) The Quaternary of the United States.Princeton University Press,Princeton, New Jersey.

- Review of Anillinus, with descriptions of 17 new species and a key to soil and litter speices (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Trechinae: Bembidiini).Coleopterists Bulletin58(2):185‑233. https://doi.org/10.1649/611

- Roadside geology of Texas.Mountain Press Publishing Company,Missoula, Montana,418pp. [ISBN0-87842-265-X]

- Vegetational history of the Ozark forest.University of Missouri Press,Columbia, Missouri,138pp.

- First records of Orchestes Fagi (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Curculioninae) in North America, with a checklist of the North American Rhamphini.Coleopterists Bulletin66(4):297‑304. https://doi.org/10.1649/072.066.0401

- Ozarks ecoregional conservation assessment.The Nature Conservancy Midwestern Resource Office,Minneapolis, Minnesota,52pp.

- Thompson RG (1979) Larvae of North American Carabidae with a key to tribes. In: Erwin TL, Ball GE, Whitehead DR, Halpern AL (Eds) Carabid beetles: Their evolution, natural history, and classification.Springer,646pp. [ISBN9400996306]. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9628-1_11

- Distributional survey of the eastern collared lizard, Crotaphytus collaris collaris (Squamata: Iguanidae), within the Arkansas River Valley of Arkansas.Proceedings of the Arkansas Academy of Science43:101‑104.

- In search of western diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) in Arkansas.Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society27(4):89‑94.

- The Amphibians and Reptiles of Arkansas.University of Arkansas Press,Fayetteville, Arkansas,440pp. [ISBN1557287384]

- Geologic Provinces of the United States: Ouachita-Ozark Interior Highlands. http://geomaps.wr.usgs.gov/parks/province/inthigh.html. Accessed on: 2015-9-07.

- The genera of the weevil family Anthribidae north of Mexico (Coleoptera).Transactions of the American Entomological Society86(1):41‑85.

- A review of Nearctic and some related Anthribidae (Coleoptera).Insecta Mundi12:251‑296.

- Valentine BD (2002) Anthribidae. In: Arnett RH, Thomas MC, Skelley PE, Franks JH (Eds) American Beetles, volume 2: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea.CRC Press,New York, New York,861pp. [ISBN0-8493-0954-9].

- The species of Cossonus Clairv. (Coleoptera) of America north of Mexico.Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society10(1):1‑23.

- A review of the genus Scaphinotus, subgenus Scaphinotus DeJean (Coleoptera-Carabidae).Entomologica Americana18:93‑133.

- Rock outcrop plant communities (glades) in the Ozarks: A synthesis.The Southwestern Naturalist47(4):585‑597. https://doi.org/10.2307/3672662