|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

Data paper

|

Fauna Europaea: Helminths (Animal Parasitic)

|

Corresponding author:

Academic editor: Lyubomir Penev

Received: 24 Jan 2014 | Accepted: 10 May 2014 | Published: 17 Sep 2014

© 2014 David Gibson, Rodney Bray, David Hunt, Boyko Georgiev, Tomaš Scholz, Philip Harris, Tor Bakke, Teresa Pojmanska, Katarzyna Niewiadomska, Aneta Kostadinova, Vasyl Tkach, Odile Bain, Marie-Claude Durette-Desset, Lynda Gibbons, František Moravec, Annie Petter, Zlatka Dimitrova, Kurt Buchmann, E. Valtonen, Yde de Jong

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Gibson D, Bray R, Hunt D, Georgiev B, Scholz T, Harris P, Bakke T, Pojmanska T, Niewiadomska K, Kostadinova A, Tkach V, Bain O, Durette-Desset M, Gibbons L, Moravec F, Petter A, Dimitrova Z, Buchmann K, Valtonen E, de Jong Y (2014) Fauna Europaea: Helminths (Animal Parasitic). Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1060. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.2.e1060

|

|

Abstract

Fauna Europaea provides a public web-service with an index of scientific names (including important synonyms) of all living European land and freshwater animals, their geographical distribution at country level (up to the Urals, excluding the Caucasus region), and some additional information. The Fauna Europaea project covers about 230,000 taxonomic names, including 130,000 accepted species and 14,000 accepted subspecies, which is much more than the originally projected number of 100,000 species. This represents a huge effort by more than 400 contributing specialists throughout Europe and is a unique (standard) reference suitable for many users in science, government, industry, nature conservation and education.

Helminths parasitic in animals represent a large assemblage of worms, representing three phyla, with more than 200 families and almost 4,000 species of parasites from all major vertebrate and many invertebrate groups. A general introduction is given for each of the major groups of parasitic worms, i.e. the Acanthocephala, Monogenea, Trematoda (Aspidogastrea and Digenea), Cestoda and Nematoda. Basic information for each group includes its size, host-range, distribution, morphological features, life-cycle, classification, identification and recent key-works. Tabulations include a complete list of families dealt with, the number of species in each and the name of the specialist responsible for data acquisition, a list of additional specialists who helped with particular groups, and a list of higher taxa dealt with down to the family level. A compilation of useful references is appended.

Keywords

Biodiversity Informatics, Fauna Europaea, Taxonomic indexing, Zoology, Biodiversity, Taxonomy, Helminth, Acanthocephala, Cestoda, Monogenea, Trematoda, Nematoda, Parasite

Introduction

The European Commission published the European Community Biodiversity Strategy, providing a framework for the development of Community policies and instruments in order to comply with the Convention on Biological Diversity. This Strategy recognises the current incomplete state of knowledge at all levels concerning biodiversity, which is a constraint on the successful implementation of the Convention. The Fauna Europaea contributes to this Strategy by supporting one of the main themes: to identify and catalogue the components of European biodiversity into a database in order to serve as a basic tool for science and conservation policies.

With regard to biodiversity in Europe, both science and policy depend on a knowledge of its components. The assessment of biodiversity, monitoring changes, sustainable exploitation of biodiversity and much legislative work depend upon a validated overview of taxonomic biodiversity. Towards this end, the Fauna Europaea plays a major role, providing a web-based information infrastructure with an index of scientific names (including important synonyms) of all living European land and freshwater animals, their geographical distribution at country level and some additional useful information. In this sense, the Fauna Europaea database provides a unique reference for many user-groups, such as scientists, governments, industries, conservation communities and educational programmes.

The Fauna Europaea started in 2000 as an EC-FP5 four-year project, delivering its first release in 2004. After 13 years of steady progress, in order to improve the dissemination of Fauna Europaea results and to increase the general awareness of work done by the Fauna Europaea contributors, novel e-Publishing tools have been used to prepare data papers for all 58 major taxonomic groups. This contribution represents the first publication of the Fauna Europaea Helminths (Animal Parasitic) data sector as a BDJ data paper.

General description

The Fauna Europaea is a database of the scientific names and distribution of all living, currently known multicellular European land and freshwater animal species assembled by a large network of experts using advanced electronic tools for data collation and validation routines.

The 'Helminths (animal parasitic)' is one of the 58 major Fauna Europaea taxonomic groups, covering 3,986 species. The data were acquired and checked by a network of 19 specialists (Tables

HELMITNTHS

The animal parasitic helminths (‘parasitic worms’) dealt with in this section include members of three phyla, the Acanthocephala (‘thorny-headed worms’ or 'spiny-headed worms'), Platyhelminthes (‘flatworms’) and Nematoda (‘roundworms’); these are usually referred to as acanthocephalans, platyhelminths and nematodes, respectively. Parasitic worms are usually parasitic at the adult stage, but many are also parasitic as larvae. Many have complex life-cycles involving the ‘definitive’ or ‘final’ host (usually a vertebrate), which harbours the adult stage, and one or more ‘intermediate hosts’ (invertebrate or vertebrate), which harbour the larval stage(s). Others have a direct life-cycle, where the definitive host is infected directly via an egg or a larval stage. Such larval stages are often encysted and survive in this state for long periods. Transmission of the parasite to the definitive host is often by ingestion with its food, or via the direct penetration by a larval stage. In nature, it is the usual condition for animals to be parasitized, so they have evolved to accommodate certain levels of infection. However, in cases where animals are kept or occur in unnaturally high concentrations, e.g. in the cases of farming, aquaculture or even man in villages or urban situations, parasite populations can build, causing them to become pathogenic. However, there are many factors, such as stress, which can cause a reduced resistance to parasites.

The classification and identification of parasitic worms have been based mainly on morphological features, although other factors, such as the host, distribution, site and life-cycle, may also be taken into consideration. In recent years, classifications based on molecular findings, which are thought to approximate closer to a true phylogenetic system, have been introduced. However, their use causes problems in identification, as classifications based on molecules and morphology are rarely totally concordant. Using a molecular classification has the disadvantage that accepted groups may not be recognised, or at least not easily recognised, using morphological criteria. Furthermore, molecular classifications are virtually always based on only an extremely small fraction of the number of taxa and individuals within the group, and consequently many taxa may be left stranded as ‘incertae sedis’. Therefore, although molecular evidence is considered in some recent classifications, taxonomic arrangements still tend to be based mainly on morphological and other biological criteria.

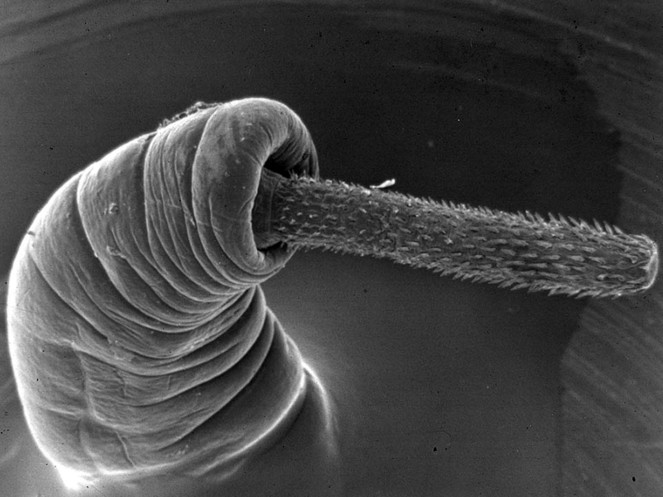

The ACANTHOCEPHALA is a relatively small group of about 1,200 species. Acanthocephalans (Fig.

In recent classifications (

The PLATYHELMINTHES (flatworms) include both free-living and parasitic groups. They are bilaterally symmetrical, lack a body cavity, are composed of three main cell layers, usually lack an anus and are usually hermaphroditic. The free-living groups, referred to as the Turbellaria, are dealt with elsewhere, but do include a small number of parasitic or commensal forms. Parasitic platyhelminths form a group called the Neodermata, which comprises three distinct, divergent classes, which have in common a specialised syncytial body-covering, the tegument or neodermis, derived from mesodermal cells. The three classes are the Monogenea, the Trematoda (‘flukes’) and the Cestoda (‘tapeworms’). These groups can be so plastic in terms of their morphology and life-history that there are usually exceptions to every rule.

The Monogenea (also referred to as the Monogenoidea by a small number of workers, but use of this name should be avoided for several reasons, a major one being that it terminates in a superfamily suffix) are a group of about 6,000-7,000 species which are mainly ectoparasitic on fishes, especially on the gills and skin, and occasionally other aquatic organisms, such as amphibians. A small number of species also occur as endoparasites. The majority of monogenean species (Fig.

Monogeneans are generally distinguished by features of their posterior attachment organ (haptor), which is normally armed with attachment clamps and/or anchors and hooks, and in some cases the structure of the sclerotised hardparts of the male and female reproductive systems is also important. Such differences between congeneric species can be very subtle. Classifications vary, but those forms where the haptor is typically armed with clamps (or suckers) and minute (vestigial) hooks are referred to the subclass Polyopisthocotylea (or Oligonchoinea + Polystomatoinea), and those armed with hooks only (some large) belong to the subclass Monopisthocotylea (or Polyonchoinea). Most polyopisthocotyleans live on the gills and feed on blood, whereas most monopisthocotyleans live on the skin or gills and tend to feed on skin and/or mucus. Recent molecular work has suggested that these two groups are independent and that the Monogenea may not be monophyletic (

The Trematoda is a large class of 15,000-20,000 species which utilise all of the major vertebrate groups as hosts. Most trematodes (flukes) are endoparasitic as adults and live in the alimentary canal, but the group is extremely adaptable in terms of site, with different species occurring in most major body cavities and organs, and a very small number being ectoparasitic. One distinctive feature of virtually all trematodes is the involvement of molluscs in their life-history. There are two subclasses, the Aspidogastrea and the Digenea.

The Aspidogastrea is a small, disparate group of fewer than 100 species, whose members occur as gut parasites of molluscs, fishes and turtles. Those in molluscs have a direct life-cycle, whereas those with vertebrate hosts, where the complete life-cycle is known, use molluscs as primary hosts, with transmission by ingestion. They generally have a relatively low level of host-specificity. There are four families, all of which possess either a large, subdivided ventral disc or a row of suckers; only one family, the Aspidogastridae, occurs in freshwater, whereas the other three families are marine. A recent key to the genera can be found in

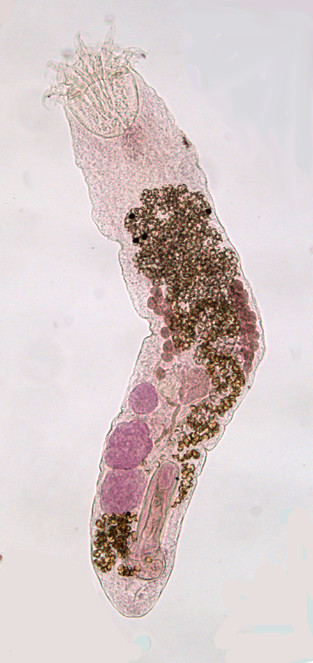

The Digenea is an enormous group of more than 2,500 nominal genera (

Digeneans are thought to generally exhibit a high level of host-specificity to the mollusc host, a low level to any intermediate host and a variable level to the final host. The form of the life-cycle can be extremely plastic in the different groups; for example, in some the cercaria can encyst on vegetation and the herbivorous final host acquires the parasite in its diet, and, in others, the life-cycle is telescoped via the parasite maturing in a host that at one time during its evolution represented an intermediate host, or is extended by the addition of another vertebrate host via the ingestion of a host that was once the final host. With regard to their morphology, digeneans are even more diverse. Although the standard pattern is for a species to have a sucker at the anterior end and another on the ventral surface, some groups have one sucker and others none at all. Some have a body form which is totally unrecognisable as a digenean to a non-specialist. Other somewhat rare variations in structure are found in groups which have an intestine with an anus or ani, and others have no gut at all. There are rare dioecious forms, forms with the entire life-cycle in one and the same host and forms which live on the gills, in the vascular system or under fish scales. Classifications vary, but recent opinion indicates the presence of only two or three orders. Although there are recent molecular phylogenies (e.g.

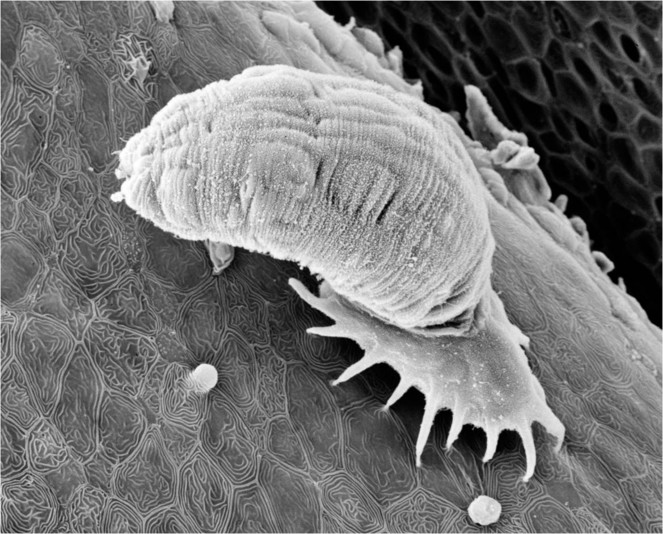

The Cestoda (tapeworms) is a relatively large (c. 8,000 species) and diverse group of parasites, the majority of which are found in the intestine of vertebrates (all groups). Like the acanthocephalans, they lack an alimentary canal and absorb their nutrients through their surface layer (tegument), which bears a dense covering of armed, villus-like structures (microtriches) that greatly increase its surface area and represent the main site for nutrient absorption. Tapeworms (Fig.

Cestodes generally have a life-cycle involving one or two intermediate hosts. Since adult cestodes are intestinal parasites of vertebrates, the eggs or gravid segments containing eggs pass out with the faeces. In those groups prevalent in terrestrial vertebrates, if the eggs are eaten by a suitable intermediate host, which may be a terrestrial invertebrate (commonly an arthropod) or a vertebrate, they hatch to release a hexacanth (six-hooked) larva, called an onchosphere. In the case of those groups more prevalent in fishes or other aquatic vertebrates, the eggs hatch in water to release a ciliated, motile hexacanth, called a coracidium, which is eaten by an aquatic arthropod intermediate host, such as a copepod. In the intermediate host, the hexacanth usually penetrates the gut wall and develops in the body-cavity into a procercoid. It then develops further, either in the same host or, in cases where the first host is eaten, in a second intermediate host, into a resting, normally encysted, stage, which takes on a variety of names, depending upon its form, e.g. cysticercus, cysticercoids or plerocercoid (

There are marked differences in the form of the attachment organ on the scolex, which form the main criteria for distinguishing the numerous (c. 15) orders of the group. Other important characters include the shape of the segments and the arrangement and form of the reproductive system(s) within the segments, e.g. the position of the genital pore, the nature of the vitellarium, the size of the cirrus-sac, the shape of the ovary and the nature of the uterus. Some of these features are also used to distinguish genera. At the specific level, the number and morphometrics of the hooks, which commonly form the armature of the scolex, are useful. The functional classification of the group is still based on morphology, but, although the basic arrangement is rather stable, molecular data indicate that some changes are needed. The ‘Keys to the Cestode Parasites of Vertebrates’ (

The phylum NEMATODA is probably the most abundant and widespread animal group, often occurring in huge numbers in environments ranging from hot springs to polar regions. In addition to free-living marine and freshwater forms, there are free-living forms in the soil and parasitic forms in both animals and plants. At least 30,000 species are known, but this is estimated to be only a very small fraction of those that exist. Nematodes (Fig.

The phylum is divided into two classes, the Adenophorea and the Secernentea, both of which have evolved parasitic members, although the majority of animal parasites belong to the latter group. Major differences between the groups reflect the presence and absence of small sensory structures (phasmids) on the tail and the nature of the excretory system. There is also a fundamental biological difference in the parasitic members, since in adenophoreans the first-stage larva is infective to the definitive (final) host, whereas in the Secernentea it is the third-stage larva.

The life-cycles of parasitic forms may be direct or indirect. Direct life-cycles may involve the ingestion of eggs or larvae with food or, in some cases, the direct penetration of larvae through the skin. Indirect life-cycles usually utilise invertebrate intermediate hosts, but sometimes vertebrates (or larger invertebrates) may act as intermediate or paratenic hosts. Such larvae usually occur, often encysted, in the tissues of intermediate hosts. The majority of nematodes parasitic in vertebrates occur in the alimentary canal; those in other parts of the body often require the migration of larvae through the body to reach these sites. Some groups with a direct life-cycle also have a larval migration from the gut and into the tissues and back to the gut; this represents the vestige of an indirect life-cycle from its evolutionary past. Whichever mode of transmission is utilised, the chance of an egg or larva developing into an adult worm is very small, but this may be compensated for by a huge output of eggs, which in some cases reaches as high as 200,000 per day from a single female worm.

Pathogenicity in the definitive host varies considerably, usually being dependent upon the size of the infection. Those, such as hookworms, which are heavily armed with teeth or other sclerotised mouthparts and browse upon the gut wall, can cause considerable damage. Similarly, forms which migrate around the body, both as adults in the tissues and as larvae (the latter termed a larva migrans), can cause serious problems, especially if they reach sensitive regions such as the brain, liver or eyes.

Features used for identification vary from group to group, but at higher taxonomic levels, the nature of the oesophagus, the form of the head (presence and number of lips, teeth, etc.) and the form of the male tail are usually important. At the specific level, details of the male tail, such as the arrangement of caudal papillae (sensory structures used during copulation) and the length and shape of the spicule or spicules (sclerotised copulatory aids) are important. In most cases, males carry more taxonomically useful information than females, such that the latter are often unidentifiable at the specific level. The most used classification of the nematodes based on morphology is that of ‘Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates’, published as a series of 10 booklets between 1974 and 1983. This has recently been re-issued as a single volume (

Project description

This BDJ data paper includes the taxonomic indexing efforts in the Fauna Europaea on European helminths covering the first two versions of Fauna Europaea worked on between 2000 and 2013 (up to version 2.6).

The taxonomic framework of Fauna Europaea includes partner institute, providing taxonomic expertise and information, and expert networks taking care of data collation.

Every taxonomic group is covered by at least one Group Coordinator responsible for the supervision and integrated input of taxonomic and distributional data for a particular group. For helminths, the responsible Group Coordinator is David Gibson (versions 1 & 2).

The Fauna Europaea checklist would not have reached its current level of completion without the input from several groups of specialists. The formal responsibility of collating and delivering the data for the relevant families rested with a number of Taxonomic Specialists (see Table

| FAMILY | NUMBER OF SPECIES | SPECIALIST(S) |

| Acanthocolpidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Acanthostomidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Acoleidae | 4 | Rodney Bray |

| Acrobothriidae | 5 | Rodney Bray |

| Acuariidae | 96 | David Gibson |

| Agfidae | 2 | David J. Hunt |

| Alirhabditidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Allantonematidae | 78 | David J. Hunt |

| Allocreadiidae | 15 | David Gibson |

| Amabiliidae | 13 | Rodney Bray |

| Amidostomidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Amphilinidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Ancylostomatidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Ancyrocephalidae | 34 | Rodney Bray |

| Angiostomatidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Angiostrongylidae | 15 | David Gibson |

| Anguillicolidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Anisakidae | 30 | David Gibson |

| Anoplocephalidae | 49 | Rodney Bray |

| Apororhynchidae | 2 | Rodney Bray |

| Aproctidae | 11 | David Gibson |

| Arhythmacanthidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Ascarididae | 34 | David Gibson |

| Ascaridiidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Aspidogastridae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Atractidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Auridistomidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Azygiidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Bothriocephalidae | 9 | Rodney Bray |

| Brachycoeliidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Brachylaimidae | 28 | David Gibson |

| Bucephalidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Bunocotylidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Camallanidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Capillariidae | 121 | David Gibson |

| Capsalidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Carabonematidae | 1 | David J. Hunt |

| Caryophyllaeidae | 15 | Rodney Bray |

| Catenotaeniidae | 7 | Rodney Bray |

| Cathaemasiidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Centrorhynchidae | 23 | David Gibson |

| Cephalochlamydidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Cephalogonimidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Chabertiidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Cladorchiidae | 6 | David Gibson |

| Clinostomidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Collyriclidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Cosmocercidae | 15 | David J. Hunt |

| Crenosomatidae | 13 | David Gibson |

| Cryptogonimidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Cucullanidae | 7 | David Gibson |

| Cyathocotylidae | 19 | Rodney Bray |

| Cyclocoelidae | 28 | David Gibson |

| Cystidicolidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Cystoopsidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Dactylogyridae | 125 | Rodney Bray |

| Daniconematidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Davaineidae | 66 | Rodney Bray |

| Derogenidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Desmidocercidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Diaphanocephalidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Diclybothriidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Dicrocoeliidae | 88 | David Gibson |

| Dictyocaulidae | 8 | David Gibson |

| Dilepididae | 201 | Rodney Bray |

| Dioctophymatidae | 9 | David Gibson |

| Dioecocestidae | 4 | Rodney Bray |

| Diphyllobothriidae | 23 | Rodney Bray |

| Diplectanidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Diplodiscidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Diplostomidae | 67 | David Gibson |

| Diplotriaenidae | 22 | Rodney Bray |

| Diplozoidae | 20 | Rodney Bray |

| Dipylidiidae | 11 | Rodney Bray |

| Discocotylidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Dracunculidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Drilonematidae | 9 | David J. Hunt |

| Echinorhynchidae | 22 | David Gibson |

| Echinostomatidae | 153 | David Gibson |

| Ektaphelenchidae | 14 | David J. Hunt |

| Entaphelenchidae | 7 | David J. Hunt |

| Eucotylidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Eumegacetidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Fasciolidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Faustulidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Filariidae | 7 | David Gibson |

| Filaroididae | 7 | David Gibson |

| Gastrodiscidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Gastrothylacidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Gigantorhynchidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Gnathostomatidae | 7 | David Gibson |

| Gongylonematidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Gorgoderidae | 30 | David Gibson |

| Gymnophallidae | 19 | David Gibson |

| Gyrodactylidae | 117 | Rodney Bray |

| Habronematidae | 24 | David Gibson |

| Haploporidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Haplosplanchnidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Hartertiidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Hedruridae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Heligmonellidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Heligmosomidae | 26 | David Gibson |

| Hemiuridae | 9 | David Gibson |

| Heterakidae | 11 | David Gibson |

| Heterophyidae | 54 | David Gibson |

| Heterorhabditidae | 4 | David J. Hunt |

| Heteroxynematidae | 14 | David Gibson |

| Hymenolepididae | 343 | Rodney Bray |

| Iagotrematidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Illiosentidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Iotonchiidae | 9 | David Gibson |

| Kathlaniidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Kiwinematidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Lecithasteridae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Lecithodendriidae | 89 | David Gibson |

| Leucochloridiidae | 15 | David Gibson |

| Leucochloridiomorphidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Lytocestidae | 9 | Rodney Bray |

| Macroderidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Mazocraeidae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Mermithidae | 34 | David J. Hunt |

| Mesocestoididae | 12 | Rodney Bray |

| Mesotretidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Metadilepididae | 3 | Rodney Bray |

| Metastrongylidae | 7 | David Gibson |

| Microcotylidae | 2 | Rodney Bray |

| Microphallidae | 54 | David Gibson |

| Molineidae | 41 | David Gibson |

| Moniliformidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Monorchiidae | 13 | David Gibson |

| Muspiceidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Nanophyetidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Nematotaeniidae | 4 | Rodney Bray |

| Neoechinorhynchidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Notocotylidae | 39 | David Gibson |

| Octomacridae | 1 | Rodney Bray |

| Oligacanthorhynchidae | 15 | David Gibson |

| Omphalometridae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Onchocercidae | 67 | David Gibson |

| Opecoelidae | 21 | David Gibson |

| Opisthorchiidae | 35 | David Gibson |

| Orchipedidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Ornithostrongylidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Oxyuridae | 28 | David Gibson |

| Pachypsolidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Panopistidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Paramphistomidae | 11 | David Gibson |

| Parasitaphelenchidae | 41 | David J. Hunt |

| Parasitylenchidae | 34 | David J. Hunt |

| Paruterinidae | 40 | Rodney Bray |

| Paurodontidae | 1 | David J. Hunt |

| Pharyngodonidae | 43 | David Gibson |

| Philometridae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Philophthalmidae | 24 | David Gibson |

| Physalopteridae | 23 | David Gibson |

| Plagiorchiidae | 91 | David Gibson |

| Plagiorhynchidae | 17 | David Gibson |

| Pneumospiruridae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Polymorphidae | 28 | David Gibson |

| Polystomatidae | 14 | Rodney Bray |

| Pomphorhynchidae | 5 | David Gibson |

| Progynotaeniidae | 8 | Rodney Bray |

| Pronocephalidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Prosthogonimidae | 12 | David Gibson |

| Proteocephalidae | 24 | Rodney Bray |

| Protostrongylidae | 25 | David Gibson |

| Pseudaliidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Pseudonymidae | 4 | David J. Hunt |

| Psilostomidae | 23 | David Gibson |

| Quadrigyridae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Quimperiidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Renicolidae | 27 | David Gibson |

| Rhabdiasidae | 11 | David Gibson |

| Rhabdochonidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Rhadinorhynchidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Rictulariidae | 13 | David Gibson |

| Robertdollfusidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Sanguinicolidae | 6 | David Gibson |

| Schistosomatidae | 19 | David Gibson |

| Seuratidae | 6 | David Gibson |

| Skrjabillanidae | 8 | David Gibson |

| Skrjabingylidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Soboliphymatidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Sphaerulariidae | 3 | David J. Hunt |

| Spirocercidae | 10 | David Gibson |

| Spirorchiidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Spiruridae | 6 | David Gibson |

| Steinernematidae | 9 | David J. Hunt |

| Stomylotrematidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Strigeidae | 45 | David Gibson |

| Strongylacanthidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| Strongylidae | 47 | David Gibson |

| Strongyloididae | 23 | David Gibson |

| Subuluridae | 16 | David Gibson |

| Syngamidae | 15 | David Gibson |

| Syrphonematidae | 1 | David J. Hunt |

| Taeniidae | 26 | Rodney Bray |

| Telorchiidae | 9 | David Gibson |

| Tenuisentidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Tetrabothriidae | 11 | Rodney Bray |

| Tetrameridae | 26 | David Gibson |

| Tetraonchidae | 6 | Rodney Bray |

| Thapariellidae | 1 | David Gibson |

| Thelastomatidae | 28 | David J. Hunt |

| Thelaziidae | 14 | David Gibson |

| Travassosinematidae | 4 | David J. Hunt |

| Triaenophoridae | 10 | Rodney Bray |

| Trichinellidae | 6 | David Gibson |

| Trichosomoididae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Trichostrongylidae | 78 | David Gibson |

| Trichuridae | 21 | David Gibson |

| Troglotrematidae | 3 | David Gibson |

| Typhlocoelidae | 4 | David Gibson |

| Zoogonidae | 2 | David Gibson |

| GROUP or AREA | OTHER SPECIALIST(S) |

| Monogenea | Philip Harris |

| Cestoda | Boyko Georgiev |

| Cestoda | Tomaš Scholz |

| Digenea | Tor Bakke |

| Digenea | Teresa Pojmanska |

| Digenea | Katarzyna Niewiadomska |

| Digenea | Aneta Kostadinova |

| Digenea | Vasyl Tkach |

| Nematoda | Odile Bain [deceased] |

| Nematoda | Marie-Claude Durette-Desset |

| Nematoda | Lynda Gibbons |

| Nematoda | František Moravec |

| Nematoda | Annie Petter |

| Acanthocephala | Zlatka Dimitrova |

| Acanthocephala | Kurt Buchmann |

| Acanthocephala | Tellervo Valtonen |

An overview of the expert network for helminths can be found here: http://www.faunaeur.org/experts.php?id=51.

Data management tasks are taken care of by the Fauna Europaea project bureau. During the project phase (until 2004) a network of principal partners took care of diverse management tasks: the Zoological Museum Amsterdam (general management & system development), the Zoological Museum of Copenhagen (data collation), the National Museum of Natural History in Paris (data validation) and the Museum and Institute of Zoology in Warsaw (NAS extension). Since the formal project ended (2004-2013), all tasks have been undertaken by the Zoological Museum Amsterdam.

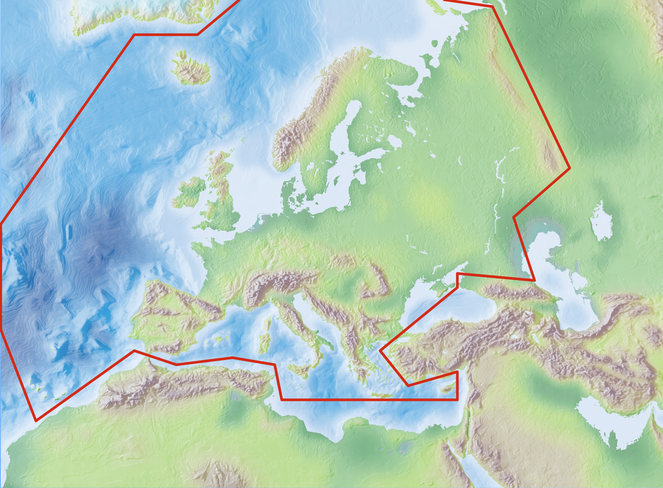

The area study covers the European mainland (Western Palaearctic), including the Macaronesian islands, and excluding the Caucasus, Turkey, the Arabian Peninsula and Northern Africa.

Standards. Group coordinators and taxonomic specialists have had to deliver the (sub)species names according to strict standards. The names provided by the Fauna Europaea (FaEu) are scientific names. The taxonomic scope includes issues such as: (1) the definition of criteria used to identify accepted species-group taxa; (2) the hierarchy (classification scheme) for the accommodation of all accepted species and (3) relevant synonyms; and (4) the correct nomenclature. The Fauna Europaea 'Guidelines for Group Coordinators and Taxonomic Specialists' includes the standards, protocols, scope and limits that provide instructions for all of the more then 400 specialists contributing to the project.

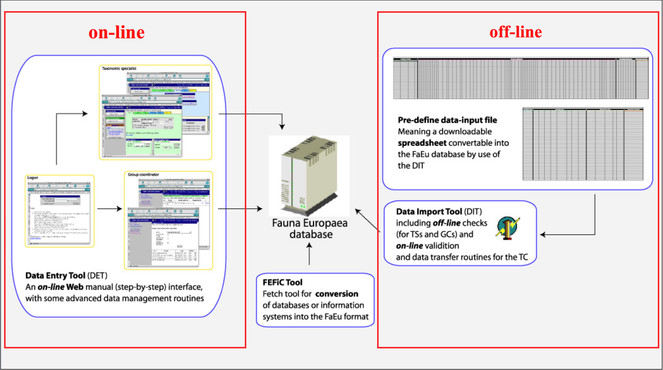

Data management. The data records could either be entered offline into a preformatted MS-Excel worksheet or directly into the Fauna Europaea transaction database using an online browser interface. The data servers are hosted at the University of Amsterdam.

Data set. The Fauna Europaea basic data set consists of: accepted (sub)species names (including authorship), synonym names (including authorship), a taxonomic hierarchy/classification, misapplied names (including misspellings and alternative taxonomic views), homonym annotations, expert details, European distribution (at the country level), Global distribution (only for European species), taxonomic reference (optional), and occurrence reference (optional).

Fauna Europaea was funded by the European Commission under various framework programs (see above).

Sampling methods

See spatial coverage and geographical coverage descriptions.

Fauna Europaea data have been assembled by principal taxonomic experts, based on their individual expertise, including literature sources, collection research and field observations. In total no less than 476 experts contributed taxonomic and/or faunistic information for the Fauna Europaea. The vast majority of the experts are from Europe (including EU non-member states). As a unique feature, Fauna Europaea funds were set aside for rewarding/compensating for the work of taxonomic specialists and group coordinators.

To facilitate data transfer and data import, sophisticated on-line (web interfaces) and off-line (spreadsheets) data-entry routines were built and integrated within an underlying central Fauna Europaea transaction database (see Fig.

A first release of the Fauna Europaea index via the web-portal has been presented at 27 th of September 2004, the most recent release (version 2.6.2) was launched at 29 August 2013. An overview of Fauna Europaea releases can be found here: http://www.faunaeur.org/about_fauna_versions.php.

Fauna Europaea data are unique in the sense that they are fully expert based. Selecting leading experts for all groups assured the systematic reliability and consistency of the Fauna Europaea data.

Furthermore, all Fauna Europaea data sets are intensively reviewed at regional and thematic validation meetings, at review sessions at taxonomic symposia (for some groups), by Fauna Europaea Focal Points (during the FaEu-NAS and PESI projects) and by various end-users sending annotations using a web form at the web-portal. Additional validation of gaps and correct spelling was effected at the validation office in Paris.

In conclusion, we expect to get taxonomic data for 99.3% of the known European fauna. The faunistic coverage is not quite as good, but nevertheless represents 90-95% of the total fauna. Recognised gaps for the helminths include: areas where the geographical divisions of the Host-Parasite Database of the Natural History Museum, London (the main source of the data), as outlined below, are not concordant with those of the Fauna Europaea. It is also likely that, although an update to include new taxa was carried out in 2006, the inclusion of recent geographical data may be limited.

Checks on the technical and logical correctness of the data have been implemented in the data entry tools, including around 50 business rules (http://dev.e-taxonomy.eu/trac/wiki/IntegrityRulesEditPESI). This validation tool proved to be of huge value for both the experts and project management, and it contributed significantly to the preparation of a remarkably clean and consistent data set. This thorough reviewing makes Fauna Europaea the most scrutinised data sets in its domain.

By evaluating the team structure and life-cycle procedures (data-entry, validation, updating, etc.), clear definitions of the roles of users and user-groups, depending on the taxonomic framework, were established, including ownership and read and writes privileges, and their changes during the project life-cycle. In addition, guidelines on common data exchange formats and codes have been issued.

Geographic coverage

Species and subspecies distributions in the Fauna Europaea are registered at least at the country level, i.e. for political countries. For this purpose, the FaEu geographical system basically follows the TDWG standards. The covered area includes the European mainland (Western Palaearctic), plus the Macaronesian islands (excl. Cape Verde Islands), Cyprus, Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya. Western Kazakhstan and the Caucasus are excluded (see Fig.

The focus is on species (or subspecies) of European multicellular animals of terrestrial and freshwater environments. Species in brackish waters, occupying the marine/freshwater or marine/terrestrial transition zones, are generally excluded.

A large proportion of the helminth records for this compilation was acquired from the Host-Parasite Database maintained by the Parasitic Worms Group at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. These data were supplemented by searches of primary and secondary literature sources and by information supplied by specialists who checked sections of the files.

There are some geographical discrepancies between the data acquired from the NHM Database and that required for the FaEu files. These are:

The Czech and Slovak Republics are included as Czechoslovakia.

The recent subdivision of Yugoslavia is not implemented.

The Irish Republic and Northern Ireland are combined.

The Ukraine and Moldova are combined.

Estonia and Latvia are combined.

European and Asian Turkey are not distinguished.

Russia is not subdivided.

In some cases these data have been adapted, but records from these areas should be treated with caution.

Mediterranean (N 35°) and Arctic Islands (N 82°) Latitude; Atlantic Ocean (Mid-Atlantic Ridge) (W 30°) and Urals (E 60°) Longitude.

Taxonomic coverage

The Fauna Europaea database contains the scientific names of all living European land and freshwater animal species, including numerous infra-groups and synonyms. More details of the conceptual background of Fauna Europaea and standards followed are described in the project description papers.

This data paper covers the Helminth (animal parasitic) content of Fauna Europaea, including 214 families, 3986 species, 32 subspecies and 435 (sub)species synonyms (see FaEu Helminths stats for a species per family chart.)

| Rank | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| kingdom | Animalia |

| subkingdom | Eumetazoa |

| phylum | Acanthocephala |

| phylum | Platyhelminthes |

| phylum | Nematoda |

| subphylum | Neodermata |

| class | Archiacanthocephala |

| class | Cestoda |

| class | Eoacanthocephala |

| class | Monogenea |

| class | Palaeacanthocephala |

| class | Trematoda |

| subclass | Aspidogastrea |

| subclass | Digenea |

| subclass | Monopisthocotylea |

| subclass | Polyopisthocotylea |

| superorder | Oligonchoinea |

| superorder | Polyonchoinea |

| superorder | Polystomatoinea |

| order | Amphilinidea |

| kingdom | Apororhynchida |

| order | Ascaridida |

| order | Aspidogastrida |

| order | Capsalidea |

| order | Caryophyllidea |

| order | Cyclophyllidea |

| order | Dactylogyridea |

| order | Diclybothriidea |

| order | Echinorhynchida |

| order | Echinostomida |

| order | Gigantorhynchida |

| order | Gyracanthocephala |

| order | Gyrodactylidea |

| order | Mazocreaidea |

| order | Moniliformida |

| order | Neoechinorhynchida |

| order | Oligacanthorhynchida |

| order | Oxyurida |

| order | Plagiorchiida |

| order | Polymorphida |

| order | Proteocephalidea |

| order | Pseudophyllidea [now Bothriocephalidea and Diphyllobothriidea] |

| order | Spathebothriidea |

| order | Strigeida |

| order | Strongylida |

| order | Tetrabothriidea |

| suborder | Aphelenchina |

| suborder | Dactylogyrinea |

| suborder | Discocotylinea |

| suborder | Hexatylina |

| suborder | Mazocraeinea |

| suborder | Microcotylinea |

| suborder | Oxyurina |

| suborder | Tetraonchinea |

| superfamily | Allocreadioidea |

| superfamily | Ancylostomatoidea |

| superfamily | Aphelenchoidea |

| superfamily | Ascaridoidea |

| superfamily | Clinostomoidea |

| superfamily | Cosmoceroidea |

| superfamily | Cyclocoeloidea |

| superfamily | Diaphanocephaloidea |

| superfamily | Diplogasteroidea |

| superfamily | Diplogastroidea |

| superfamily | Diplostomoidea |

| superfamily | Drilonematoidea |

| superfamily | Echinostomatoidea |

| superfamily | Gymnophalloidea |

| superfamily | Hemiuroidea |

| superfamily | Heterakoidea |

| superfamily | Iotonchioidea |

| superfamily | Lepocreadioidea |

| superfamily | Mermithoidea |

| superfamily | Metastrongyloidea |

| superfamily | Microphalloidea |

| superfamily | Notocotyloidea |

| superfamily | Opisthorchioidea |

| superfamily | Oxyuroidea |

| superfamily | Paramphistomoidea |

| superfamily | Plagiorchioidea |

| superfamily | Rhabditoidea |

| superfamily | Schistosomoidea |

| superfamily | Seuratoidea |

| superfamily | Sphaerularioidea |

| superfamily | Strongyloidea |

| superfamily | Subuluroidea |

| superfamily | Tetradonematoidea |

| superfamily | Thelastomatoidea |

| superfamily | Trichostrongyloidea |

| superfamily | Troglotrematoidea |

| superfamily | Zoogonoidea |

| family | Acanthocolpidae |

| family | Acanthostomidae [now syn. of Cryptogonimidae] |

| family | Acoleidae |

| family | Acrobothriidae |

| family | Acuariidae |

| family | Agfidae |

| family | Alirhabditidae |

| family | Allantonematidae |

| family | Allocreadiidae |

| family | Amabiliidae |

| family | Amidostomidae |

| family | Amphilinidae |

| family | Ancylostomatidae |

| family | Ancyrocephalidae |

| family | Angiostomatidae |

| family | Angiostrongylidae |

| family | Anguillicolidae |

| family | Anisakidae |

| family | Anoplocephalidae |

| family | Apororhynchidae |

| family | Aproctidae |

| family | Arhythmacanthidae |

| family | Ascarididae |

| family | Ascaridiidae |

| family | Aspidogastridae |

| family | Atractidae |

| family | Auridistomidae |

| family | Azygiidae |

| family | Bolbocephalodidae [treated as syn. of Strigeidae, but now recognised] |

| family | Bothriocephalidae |

| family | Brachycoeliidae |

| family | Brachylaimidae |

| family | Bucephalidae |

| family | Bunocotylidae |

| family | Camallanidae |

| family | Capillariidae |

| family | Capsalidae |

| family | Carabonematidae |

| family | Caryophyllaeidae |

| family | Catenotaeniidae |

| family | Cathaemasiidae |

| family | Centrorhynchidae |

| family | Cephalochlamydidae |

| family | Cephalogonimidae |

| family | Chabertiidae |

| family | Cladorchiidae |

| family | Clinostomidae |

| family | Collyriclidae |

| family | Cosmocercidae |

| family | Crenosomatidae |

| family | Cryptogonimidae |

| family | Cucullanidae |

| family | Cyathocotylidae |

| family | Cyclocoelidae |

| family | Cystidicolidae |

| family | Cystoopsidae |

| family | Dactylogyridae |

| family | Daniconematidae |

| family | Davaineidae |

| family | Derogenidae |

| family | Deropristidae [treated as syn. of Acanthocolpidae, but now recognised] |

| family | Desmidocercidae |

| family | Diaphanocephalidae |

| family | Diclybothriidae |

| family | Dicrocoeliidae |

| family | Dictyocaulidae |

| family | Dilepididae |

| family | Dioctophymatidae |

| family | Dioecocestidae |

| family | Diphyllobothriidae |

| family | Diplectanidae |

| family | Diplodiscidae |

| family | Diplostomidae |

| family | Diplotriaenidae |

| family | Diplozoidae |

| family | Dipylidiidae |

| family | Discocotylidae |

| family | Dracunculidae |

| family | Drilonematidae |

| family | Echinorhynchidae |

| family | Echinostomatidae |

| family | Ektaphelenchidae |

| family | Entaphelenchidae |

| family | Eucotylidae |

| family | Eumegacetidae |

| family | Fasciolidae |

| family | Faustulidae |

| family | Filariidae |

| family | Filaroididae |

| family | Gastrodiscidae |

| family | Gastrothylacidae |

| family | Gigantorhynchidae |

| family | Gnathostomatidae |

| family | Gongylonematidae |

| family | Gorgoderidae |

| family | Gymnophallidae |

| family | Gyrodactylidae |

| family | Habronematidae |

| family | Haplometridae [syn. of Plagiorchiidae] |

| family | Haploporidae |

| family | Haplosplanchnidae |

| family | Hartertiidae |

| family | Hedruridae |

| family | Heligmonellidae |

| family | Heligmosomidae |

| family | Hemiuridae |

| family | Heterakidae |

| family | Heterophyidae |

| family | Heterorhabditidae |

| family | Heteroxynematidae |

| family | Hymenolepididae |

| family | Iagotrematidae |

| family | Illiosentidae |

| family | Iotonchiidae |

| family | Kathlaniidae |

| family | Kiwinematidae |

| family | Lecithasteridae |

| family | Lecithodendriidae |

| family | Leucochloridiidae |

| family | Leucochloridiomorphidae |

| family | Lytocestidae |

| family | Macroderidae |

| family | Mazocraeidae |

| family | Mermithidae |

| family | Mesocestoididae |

| family | Mesotretidae |

| family | Metadilepididae |

| family | Metastrongylidae |

| family | Microcotylidae |

| family | Microphallidae |

| family | Molineidae |

| family | Moniliformidae |

| family | Monorchiidae |

| family | Muspiceidae |

| family | Nanophyetidae |

| family | Nematotaeniidae |

| family | Neoechinorhynchidae |

| family | Notocotylidae |

| family | Octomacridae |

| family | Oligacanthorhynchidae |

| family | Omphalometridae |

| family | Onchocercidae |

| family | Opecoelidae |

| family | Opisthorchiidae |

| family | Orchipedidae |

| family | Ornithostrongylidae |

| family | Oxyuridae |

| family | Pachypsolidae |

| family | Panopistidae |

| family | Paramphistomidae |

| family | Parasitaphelenchidae |

| family | Parasitylenchidae |

| family | Paruterinidae |

| family | Paurodontidae |

| family | Pharyngodonidae |

| family | Philometridae |

| family | Philophthalmidae |

| family | Physalopteridae |

| family | Plagiorchiidae |

| family | Plagiorchiidae |

| family | Plagiorhynchidae |

| family | Pneumospiruridae |

| family | Polymorphidae |

| family | Polystomatidae |

| family | Pomphorhynchidae |

| family | Progynotaeniidae |

| family | Pronocephalidae |

| family | Prosthogonimidae |

| family | Proteocephalidae |

| family | Protostrongylidae |

| family | Pseudaliidae |

| family | Pseudonymidae |

| family | Psilostomidae |

| family | Quadrigyridae |

| family | Quimperiidae |

| family | Renicolidae |

| family | Rhabdiasidae |

| family | Rhabdochonidae |

| family | Rhadinorhynchidae |

| family | Rictulariidae |

| family | Robertdollfusidae |

| family | Sanguinicolidae |

| family | Schistosomatidae |

| family | Seuratidae |

| family | Skrjabillanidae |

| family | Skrjabingylidae |

| family | Soboliphymatidae |

| family | Sphaerulariidae |

| family | Spirocercidae |

| family | Spirorchiidae |

| family | Spiruridae |

| family | Steinernematidae |

| family | Stomylotrematidae |

| family | Strigeidae |

| family | Strigeidae |

| family | Strongylacanthidae |

| family | Strongylidae |

| family | Strongyloididae |

| family | Subuluridae |

| family | Syngamidae |

| family | Syrphonematidae |

| family | Taeniidae |

| family | Telorchiidae |

| family | Tenuisentidae |

| family | Tetrabothriidae |

| family | Tetrameridae |

| family | Tetraonchidae |

| family | Thapariellidae |

| family | Thelastomatidae |

| family | Thelaziidae |

| family | Travassosinematidae |

| family | Triaenophoridae |

| family | Trichinellidae |

| family | Trichosomoididae |

| family | Trichostrongylidae |

| family | Trichuridae |

| family | Troglotrematidae |

| family | Typhlocoelidae |

| family | Zoogonidae |

Temporal coverage

Usage rights

The Fauna Europaea license for use is CC BY.

For more IPR details see: http://www.faunaeur.org/copyright.php.

Data resources

| Column label | Column description |

|---|---|

| datasetName | The name identifying the data set from which the record was derived (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/datasetName). |

| version | Release version of data set. |

| versionIssued | Issue data of data set version. |

| rights | Information about rights held in and over the resource (http://purl.org/dc/terms/rights). |

| rightsHolder | A person or organization owning or managing rights over the resource (http://purl.org/dc/terms/rightsHolder). |

| accessRights | Information about who can access the resource or an indication of its security status (http://purl.org/dc/terms/accessRights). |

| taxonID | An identifier for the set of taxon information (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/taxonID) |

| parentNameUsageID | An identifier for the name usage of the direct parent taxon (in a classification) of the most specific element of the scientificName (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/parentNameUsageID). |

| scientificName | The full scientific name, with authorship and date information if known (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/scientificName). |

| acceptedNameUsage | The full name, with authorship and date information if known, of the currently valid (zoological) taxon (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/acceptedNameUsage). |

| originalNameUsage | The original combination (genus and species group names), as firstly established under the rules of the associated nomenclaturalCode (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/originalNameUsage). |

| family | The full scientific name of the family in which the taxon is classified (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/family). |

| familyNameId | An identifier for the family name. |

| genus | The full scientific name of the genus in which the taxon is classified (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/genus). |

| subgenus | The full scientific name of the subgenus in which the taxon is classified. Values include the genus to avoid homonym confusion (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/subgenus). |

| specificEpithet | The name of the first or species epithet of the scientificName (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/specificEpithet). |

| infraspecificEpithet | The name of the lowest or terminal infraspecific epithet of the scientificName, excluding any rank designation (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/infraspecificEpithet). |

| taxonRank | The taxonomic rank of the most specific name in the scientificName (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/infraspecificEpithet). |

| scientificNameAuthorship | The authorship information for the scientificName formatted according to the conventions of the applicable nomenclaturalCode (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/scientificNameAuthorship). |

| authorName | Author name information |

| namePublishedInYear | The four-digit year in which the scientificName was published (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/namePublishedInYear). |

| Brackets | Annotation if authorship should be put between parentheses. |

| nomenclaturalCode | The nomenclatural code under which the scientificName is constructed (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/nomenclaturalCode). |

| taxonomicStatus | The status of the use of the scientificName as a label for a taxon (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/taxonomicStatus). |

| Column label | Column description |

|---|---|

| datasetName | The name identifying the data set from which the record was derived (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/datasetName). |

| version | Release version of data set. |

| versionIssued | Issue data of data set version. |

| rights | Information about rights held in and over the resource (http://purl.org/dc/terms/rights). |

| rightsHolder | A person or organization owning or managing rights over the resource (http://purl.org/dc/terms/rightsHolder). |

| accessRights | Information about who can access the resource or an indication of its security status (http://purl.org/dc/terms/accessRights). |

| taxonName | The full scientific name of the higher-level taxon |

| scientificNameAuthorship | The authorship information for the scientificName formatted according to the conventions of the applicable nomenclaturalCode (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/scientificNameAuthorship). |

| taxonRank | The taxonomic rank of the most specific name in the scientificName (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/infraspecificEpithet). |

| taxonID | An identifier for the set of taxon information (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/taxonID) |

| parentNameUsageID | An identifier for the name usage of the direct parent taxon (in a classification) of the most specific element of the scientificName (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/parentNameUsageID). |

Acknowledgements

Many of the records for this study were acquired from the Host-Parasite Database maintained by the Parasitic Worms Group at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. We are especially grateful to Eileen Harris and Charles Hussey, who helped Rodney Bray and David Gibson maintain this database over numerous years. We would also like to express our gratitude to those who have provided or checked additional data. Gergana Vasileva and Andrew Shinn kindly helped with the illustrations.

References

- Classification of the Acanthocephala.Folia Parasitologia60:273‑305.

- Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Archival Volume.CABI,Wallingford,424pp.

- Phylogeny and a revised classification of the Monogenoidea Bychowsky, 1937 (Platyhelminthes).Systematic Parasitology26(1):1‑32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00009644

- Keys to the Trematoda.Vol. 3.CABI,Wallingford,824pp.

- The terminology of larval cestodes or metacestodes.Systematic Parasitology52(1):1‑33.

- Keys to the Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Supplementary Volume.CABI,Wallingford,424pp.

- Gibson DI (2002) Class Trematoda Rudolphi, 1808. In: Gibson DI, Jones A, Bray RA (Eds) Keys to the Trematoda.Vol. 1.CABI,Wallingford,1-3pp.

- Keys to the Trematoda.Vol. 1.CABI,Wallingford,521pp.

- A catalogue of the nominal species of the monogenean genus Dactylogyrus Diesing, 1850 and their host genera.Systematic Parasitology35(1):3‑48.

- Nominal species of the genus Gyrodactylus von Nordmann 1832 (Monogenea: Gyrodactylidae), with a list of principal host species.Systematic Parasitology59(1):1‑27.

- Keys to the Trematoda.Vol. 2.CABI,Wallingford,745pp.

- Keys to the cestode parasites of vertebrates.CABI,Wallingford,751pp. [ISBN0 85198 879 2]

- Revision of the order Bothriocephalidea Kuchta, Scholz, Brabec & Bray, 2008 (Eucestoda) with amended generic diagnoses and keys to families and genera.Systematic Parasitology71(2):81‑136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-008-9153-7

- Suppression of the tapeworm order Pseudophyllidea (Platyhelminthes: Eucestoda) and the proposal of two new orders, Bothriocephalidea and Diphyllobothriidea.International Journal for Parasitology38(1):49‑55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.08.005

- An improved molecular phylogeny of the Nematoda with special emphasis on marine taxa.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution42(3):622‑636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.025

- Monks S, Richardson DJ (2011) Phylum Acanthocephala Kohlreuther, 1771. In: Zhang Z- (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness.Zootaxa,3148.Mapress,Auckland,234-237pp.

- Phylogeny of the Ascaridoidea (Nematoda: Ascaridida) based on three genes and morphology: hypotheses of structural and sequence evolution.Journal of Parasitology86:380.

- Interrelationships and Evolution of the Tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoda).Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution19(3):443‑467. https://doi.org/10.1006/mpev.2001.0930

- Phylogeny and classification of the Digenea (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda).International Journal for Parasitology33(7):733‑755. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00049-3

- Closing the mitochondrial circle on paraphyly of the Monogenea (Platyhelminthes) infers evolution in the diet of parasitic flatworms.International Journal for Parasitology40(11):1237‑1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.02.017

- CIH Key to the Groups and Genera of Nematode Parasites of Invertebrates.CABI,43pp.

- Rohde K (2002) Subclass Aspidogastrea Faust & Tang, 1936. In: Gibson DI, Jones A, Bray RA (Eds) Keys to the Trematoda. Vol. 1.1.CABI,Wallingford,5-14pp.

- A molecular phylogeny of the Dactylogyridae sensu Kritsky & Boeger (1989) (Monogenea) based on the D1-D3 domains of large subunit rDNA.Parasitology133(1):43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006009942

- Adding resolution to ordinal level relationships of tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoda) with large fragments of mtDNA.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution63(3):834‑847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.02.020

- Added resolution among ordinal level relationships of tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoda) with complete small and large subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA genes.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution45(1):311‑325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2007.03.019

- Phylogenetic analyses of endoparasitic Acanthocephala based on mitochondrial genomes suggest secondary loss of sensory organs.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution66(1):182‑189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2012.09.017