|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

Taxonomic Paper

|

|

Corresponding author: Brian V. Brown (bbrown@nhm.org)

Academic editor: Torsten Dikow

Received: 20 Nov 2017 | Accepted: 08 Jan 2018 | Published: 24 Jan 2018

© 2018 Brian Brown

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Brown B (2018) A second contender for “world’s smallest fly” (Diptera: Phoridae). Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e22396. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.6.e22396

|

|

Abstract

Background

Flies of the family Phoridae (Insecta: Diptera) are amongst the most diverse insects in the world, with an incredible array of species, structures and life histories. Wiithin their structural diversity is the world's smallest fly, Euryplatea nanaknihali Brown, 2012.

New information

A second minute, limuloid female phorid parasitoid fly (Diptera: Phoridae) is described. Known from a single specimen from a site near Manaus, Brazil, Megapropodiphora arnoldi gen. n., sp. n. is only 0.395 mm in body length, slightly smaller than the currently recognised smallest fly, Euryplatea nanaknihali from Thailand. The distinctive body shape of M. arnoldi, particularly the relatively enormous head, mesothorax and scutellum, the latter of which covers most of the abdomen, easily separates it from other described phorids. Most remarkably, the forelegs are extremely enlarged, whereas mid- and hind legs are reduced to small, possibly vestigial remnants. A possible male specimen, unfortunately destroyed during processing, is briefly described.

Keywords

tropical, parasitoid, biodiversity, taxonomy

Introduction

There are few other families of insects with such a wide variety of body forms and life histories as the Phoridae, humpbacked or scuttle flies. Particularly in tropical forests, there is always the possibility of discovering a new, jaw-droppingly bizarre species, or one that has incredibly specialised food and mate acquisition behaviour. Phorids are found nearly everywhere on earth, in faunas of seemingly endless numbers of species. They have such a litany of modified body parts and have conquered such a wide range of food sources that we are running out of superlatives to characterise the family.

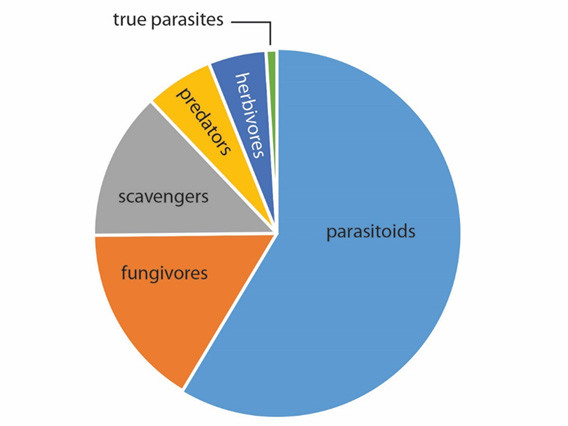

Although phorids are commonly described as scavengers, with a few parasitoid species, this generalisation is false. The “scavenger” moniker commonly affixed to phorids is based largely on the ubiquity and abundance of Megaselia scalaris (Loew, 1866), a cosmopolitan, synanthropic and highly polyphagous species (

Previously, one of the most unusual and remarkable phorids ever discovered was described, the minute (0.4 mm body length) female of Euryplatea nanaknihali from Thailand (

Materials and methods

The specimen described herein was collected by a Malaise trap (

Taxon treatments

Megapropodiphora , gen. n.

Type species

Description

Same as for species.

Diagnosis

There are a small number of minute, limuloid phorid genera in the world. In the New World tropics, the only relatively similar genera have large, differentiated frontal setae that are several times longer than the short frontal setae and do not have the scutellum covering the abdomen (

Megapropodiphora arnoldi , sp. n.

-

genus: Megapropodiphora; specificEpithet:arnoldi; scientificNameAuthorship:Brown 2018; country:Brazil; stateProvince:Amazonas; locality:12 km S Novo Airão; verbatimElevation:34 m; locationRemarks:forest; decimalLatitude:-02.71; decimalLongitude:-60.95; samplingProtocol:Malaise trap; eventDate:2013-12-08/2013-12-09; sex:female; lifeStage:adult; preparations:mounted on slide in Canada Balsam by B. Browns; recordedBy:D. Amorim, J. Raphael

-

otherCatalogNumbers:

LACM ENT 334268

Description

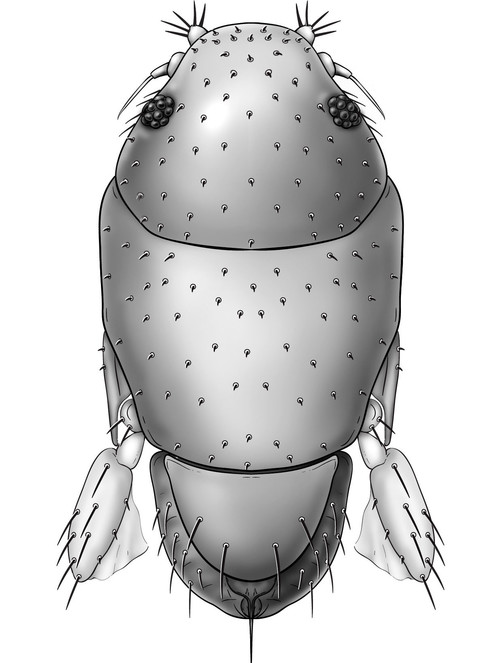

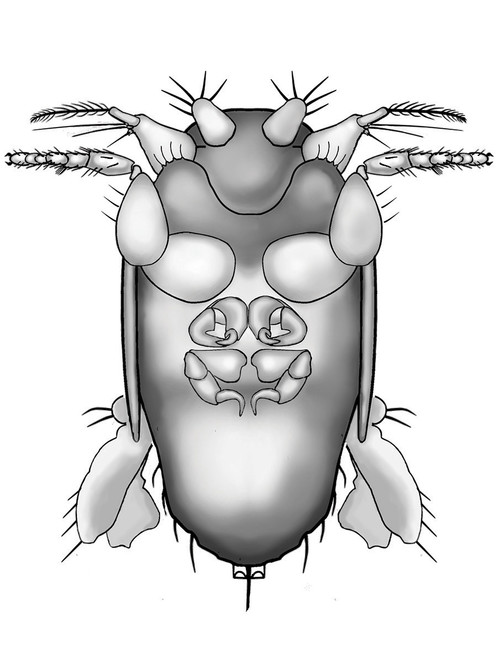

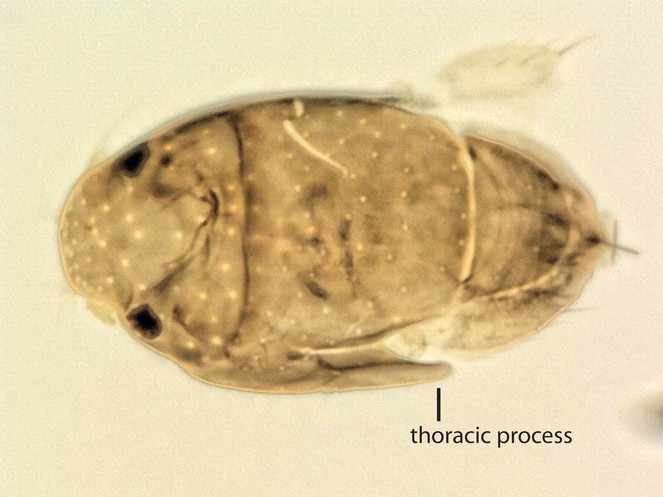

Female (Figs

Male unknown (but see below).

Diagnosis

Female. Minute, limuloid; body setae scattered, sparse; wing with shed blades and short costa; head and scutum large, scutellum covering almost entire abdomen; oviscape thin, pointed, indicating a parasitoid lifestyle. Edge of scutum lateroventrally extended, posteriorly ending in narrowed flange (Fig.

Similar genera. Males of Brachycosta Prado, 1976, have a short costa, but much longer than that of Megapropodiphora gen. n., are much larger in size and have a larger frons and head. Females of this new genus are differentiated from all other phorids by minute size, leg structure and elongation of the scutellum to cover the abdomen.

Etymology

The genus name is Latin for large foreleg, referring to the structure of the female. The specific epithet refers to Arnold Schwarzenegger, former governor of California, whose own greatly enlarged forelimbs distinguished him in his pre-political careers.

Distribution

Amazonian Brazil

Biology

Unknown, but almost certainly a parasitoid. The torn wing membrane is reminiscent of other phorid flies that shed their wings when entering a social insect colony. It seems likely that the greatly enlarged forelegs are used to clutch a host, upon which the small, rounded body would appear similar to that of many phoretic mites.

Notes

A potential male specimen was accidentally destroyed during illustration process, but from memory only, it was as follows: minute, with small head; frons greatly reduced (as in male Chonocephalus Wandolleck, 1989) and extremely reduced head setae; wing with short costa and large blade. Lacking further information, I cannot assign this new genus and species to any subfamily.

It is common for researchers to change the alcohol in Malaise trap samples, pouring off the old liquid, stained yellow with body fluids of the many preserved insects. Also, we commonly drain the alcohol out of samples for safer or at least more legal transport of these chemicals. Fortunately, the samples including the M. arnoldi sp. n. were examined immediately after being collected and were thus not so treated. The tiny phorid flies described herein are easily lost when waste alcohol is drained off, such that any alcohol that is being disposed should be first examined carefully under a microscope. Furthermore, I suggest purposely “washing” Malaise trap samples in fresh alcohol to clean tiny insects off of the larger ones and search for further microfauna.

Acknowledgements

I thank D. Amorim, J. Raphael, W. Porras, G. Kung, and all my colleagues from the 2013 expedition to Manuas for their help and camaraderie in the field. I am further grateful to L. Chiappe (LACM Research & Collections Division) for moral and financial support. Field work in Brazil also has been funded by R. Lavenberg. Illustrations were skilfully provided by I. Strazhnik and T. Hayden.

References

- Convergent adaptations in Phoridae (Diptera) living in the nests of social insects: a review of the New World Aenigmatiinae.Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada165:115‑137. https://doi.org/10.4039/entm125165115-1

- Small size no protection for acrobat ants: world's smallest fly is a parasitic phorid (Diptera: Phoridae).Annals of the Entomological Society of America105(4):550‑554. https://doi.org/10.1603/AN12011

- Scuttle flies: the Phoridae.Chapman and Hall,London.

- Natural history of the scuttle fly, Megaselia scalaris.Annual Review of Entomology53:39‑60. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093415

- A light-weight Malaise trap.Entomological News83:239‑247.