|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

Research Article

|

|

Corresponding author: Derek Sikes (dssikes@alaska.edu)

Academic editor: Robert Blakemore

Received: 13 Jun 2018 | Accepted: 01 Jul 2018 | Published: 10 Jul 2018

© 2018 Megan Booysen, Derek Sikes, Matthew Bowser, Robin Andrews

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Booysen M, Sikes D, Bowser M, Andrews R (2018) Earthworms (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae) of Interior Alaska. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e27427. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.6.e27427

|

|

Abstract

Earthworms in the family Lumbricidae in Alaska, which are known from coastal regions, primarily in south-central and south-eastern Alaska, are thought to be entirely non-native and have been shown to negatively impact previously earthworm-free ecosystems in study regions outside of Alaska. Despite occasional collections by curious citizens, there had not been a standardised earthworm survey performed in Interior Alaska and no published records exist of earthworms species from this region. Mustard extraction was used to sample six locations that differed in elevation, mostly in the College region of Fairbanks, Alaska. Two of the six locations yielded earthworms. There was no relationship between earthworm abundance and elevation (p = 0.087), although our sample size was small. Our sampling, combined with specimens in the University of Alaska Museum, has documented four exotic species and one presumed native species of lumbricid earthworms in Interior Alaska.

Keywords

Clitellata, Megadrili

Introduction

Most earthworms found in previously glaciated areas of North America are thought to be invasive (

Human activity has been the primary method for introduction of peregrine European and Asian earthworms into previously earthworm-free ecosystems (

Non-native earthworms' dramatic negative impacts on previously earthworm-free ecosystems have been well documented in temperate and boreal landscapes (

Earthworms consume organic matter and incorporate it into deeper soil layers affecting carbon, phosphorus and nitrogen availability and flux (

Rare anecdotal reports of earthworms in Interior Alaska exist and specimens have been donated to the University of Alaska Museum, but very little was known about which species occur in Interior Alaska and no published records existed. Conventional wisdom of gardeners and long-time residents of Fairbanks is that the climate is too cold for earthworms. By combining standardised sampling with opportunistically donated museum specimens, this study documents for the first time the presence, identity and distribution of lumbricid earthworms in Interior Alaska. We hypothesised that earthworms would occur more often at higher elevations due to the common presence of permafrost-cooled soils in lower elevation valleys of Interior Alaska.

Methods

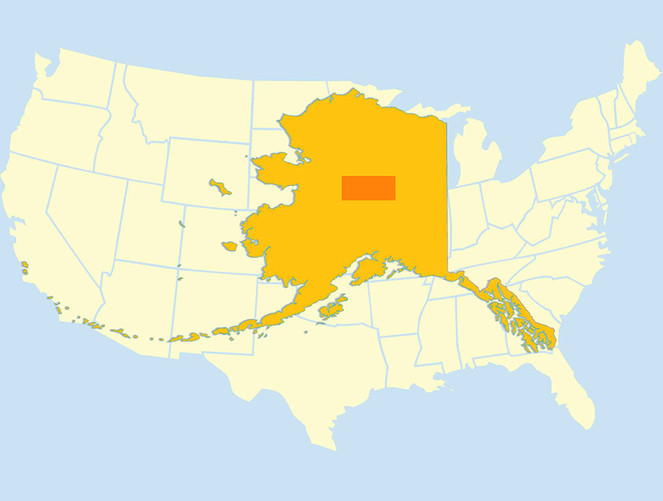

We restricted the study area to a subset of Interior Alaska as defined by the map in Fig.

Map showing study region (dark orange rectangle) of Interior Alaska, centred around the city of Fairbanks, superimposed on map of the contiguous US states for scale. Original map by Laubenstein Ronald, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is in the public domain.

Interior Alaska is dominated by boreal forest underlain with discontinuous permafrost and has a continental climate. The forest contains varying mixtures of conifers and deciduous trees including black spruce (Picea mariana (Mill.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenburg), which is abundant on permafrost soils in lowlands, white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss), Alaska paper birch (Betula pendula subsp. mandshurica (Regel) Ashburner & McAll.) and trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.), which are abundant on warmer, drier, uplands, amongst other tree and shrub species (

Since earthworms are thought to be most active during the spring and the fall (autumn) months (

| Site number | Site name | Latitude (°) | Longitude (°) | Habitat | Date | Elevation (m) |

| 1 | Booysen home | 64.82525 | -147.903 | permafrost ground | 10-Sep-17 | 132 |

| 2 | UAF campus | 64.8511 | -147.841 | lawn edged with forest, side of road | 14-Sep-17 | 142 |

| 3 | UAF campus | 64.86035 | -147.837 | forest near cemented trail | 20-Sep-17 | 185 |

| 4 | Sweeney and Mills home | 64.8419 | -147.851 | lawn | 21-Sep-17 | 134 |

| 5 | West Valley HS | 64.85091 | -147.82 | lawn near planted trees | 2-Oct-17 | 132 |

| 6 | UAF campus | 64.85509 | -147.835 | playing field, grass | 3-Oct-17 | 140 |

We used a mustard extraction method (

We identified specimens in the UAM collection and those from our standardised sampling using the key in

Results

The standardised sampling yielded one earthworm specimen that appeared to be Bimastos rubidus from site #2 and eight specimens of Dendrobaena octaedra (Table

Earthworm (Lumbricidae) records in Interior Alaska as of May 4, 2018. Year column indicates the earliest year of identification to species of Interior Alaska specimens; n indicates the number of Interior Alaska sites known for each species.

| Species | Identified by | Year of Identification | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aporrectodea caliginosa (Savigny, 1826) | M. Bowser | 2018 | 1 |

| Eiseniella tetraedra (Savigny, 1826) | M. Bowser, M. Booysen | 2016 | 1 |

| Dendrobaena octaedra (Savigny, 1826) | M. Booysen, M. Bowser | 2017 | 1 |

| Bimastos rubidus (Savigny, 1826) | M. Bowser, M. Booysen, D. S. Sikes | 2016 | 5 |

| Lumbricus terrestris Linnaeus, 1758 | D. S. Sikes, M. Booysen | 2015 | 1 |

Two specimen identifications were made using molecular data: those of Aporrectodea caliginosa and Bimastos rubidus (known as Dendrodrilus rubidus prior to

The COI sequence from our specimen of A. caliginosa from Fairbanks was 100% similar (p-dist) to sequences of A. caliginosa in BOLD BIN (

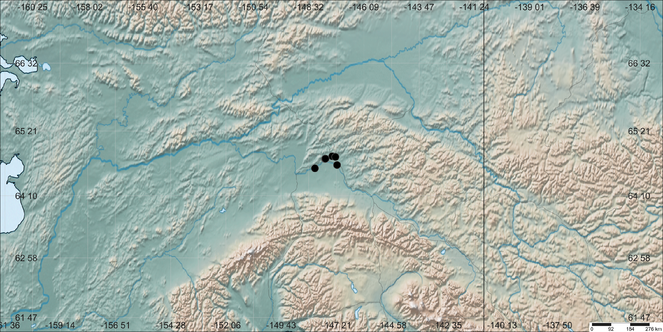

Eight locality records (Fig.

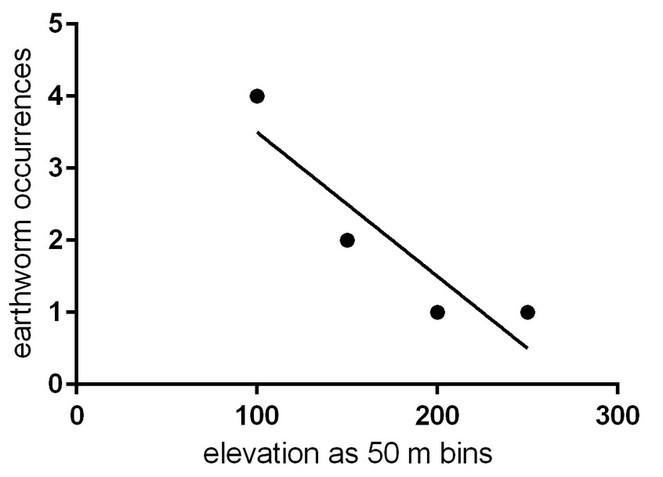

There was no significant relationship between elevation and earthworm presence when UAM data were combined with our standardised sampling data (R2 = 0.8333, p = 0.087, Fig.

Discussion

As a result of this study, five species of lumbricid earthworms have been identified as occurring in Interior Alaska. Four of these species were documented from opportunistic collections, with the standardised sampling adding one species, Dendrobaena octaedra. At least four of these species are European, or potentially Asian, introductions to North America (

There is evidence that Bimastos rubidus, Dendrobaena octaedra and Eiseniella tetraedra are established in Interior Alaska, either due to numerous worms having been collected and/or observed at one site or one species having been collected at multiple sites. The Lumbricus terrestris and Aporrectodea caliginosa records from Interior Alaska are currently based on single specimens each from single sites, which we consider insufficient evidence to assume establishment.

We do not know when these species became established. Anecdotal reports of earthworms around Fairbanks suggest that some might date into the 1990s or earlier and, given there is evidence of Bimastos rubidus from >7,000 year old lake sediment in Ontario, Canada (

Our records of L. terrestris and A. caliginosa in Interior Alaska at 64.9°N latitude are apparently the northernmost records of these species in North America to date. In the Palearctic, L. terrestris has been collected at 69.7°N (

It should be noted that some confusion exists regarding the taxonomy of members of the Aporrectodea caliginosa species complex.

The L3 lineage of A. caliginosa, to which our specimen belongs, is of European origin and appears to have become widespread relatively recently (

We hypothesised that earthworms would be more likely to occur at higher elevations, away from permafrost valleys. There was no significant relationship between elevation and earthworm presence, although there was a tendency for worms to be more commonly found at lower elevations. However, with so few samples across an elevational gradient, it would be premature to draw firm conclusions. The greater number of earthworm records at lower elevations could simply be due to greater search effort spent at lower elevations.

We expected that earthworms would be more abundant in forested land than in developed or cultivated lands like fields and lawns, but this was not supported by our findings. The two sites that yielded earthworms in our standardised sampling were both grassy lawns. One had hard, compacted and rocky soil on a playing field on the UAF campus and the other had loose soil at the edge of a forest at the base of a hill on the UAF campus. None of the forested sites in our standardised sampling yielded earthworms, nor did other grassy sites. This suggests that, despite the favourable conditions in relatively undisturbed forest with higher moisture, loose soil, ample detritus, low traffic, lack of pesticides and shade, the grassy lawns may have been near where they were introduced. Worms may have been introduced to more disturbed areas due to landscaping or may be discarded fishing bait. This suggests the worms simply have not spread far beyond their original release sites.

However, the site at which Eiseniella tetraedra was collected is an early successional alder stand along the Tanana River, relatively far from human occupation (10.7 km downstream from a farm and 20.5 km downstream from the city of Fairbanks). Earthworms were observed in litter samples from this site in both summer 2016 and 2017 (personal observation RA). This parthenogenic species is known to disperse via flowing water (

Knowing which exotic earthworm species are present, in addition to where they occur, provides important information on Alaska’s changing ecosystems, creates a present-day baseline with which to compare in the future and can help environmentalists determine if intervention and/or education needs to occur where human activity might be the leading cause of the spread of exotic earthworms. This study is a preliminary effort. We hope to expand our sampling efforts to better understand the earthworm fauna of Interior Alaska.

Data Resources

The specimen data for the vouchers supporting the species presented in Fig.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cyndie Beale, West Valley High School, for encouragement, support and help with this project which was performed as part of the 33rd annual Alaska Statewide High School Science Symposium. We thank Barney Booysen, Debra Booysen and Hannah Mills for their help with field work. We also thank those who collected earthworm specimens: Karen L. Jensen, Mary Liston and Julie Riley.

Author contributions

Megan Booysen, under Derek Sikes' mentorship, conducted the standardised sampling, identified specimens and drafted the article. Derek Sikes collected specimens and solicited specimens from citizens, curated the specimens and data, identified specimens and helped write the article. Matthew Bowser helped with identifications of specimens via both morphological and molecular analyses and helped write the article. Robin Andrews collected specimens and helped write the article. The contents of this article are the work of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any government entity. Editorial suggestions by Csaba Csuzdi and Robert Blakemore greatly improved the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Temperature Changes in Alaska. http://climate.gi.alaska. edu/ClimTrends/Change/TempChange.html. Accessed on: 2018-5-24.

- Behan VM (1978) Diversity, distribution and feeding habits of North American arctic soil Acari. Ph.D. thesis.McGill University,Montreal.

- On Bimastos parvus (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae) from Yukon Territory (Canada), with discussion of distribution of the earth- worms in northwestern North America and northeastern Siberia.Megadrilogica5:113‑116.

- American earthworms (Oligochaeta) from north of the Rio Grande - a species checklist. http://www.annelida.net/earthworm/American%20Earthworms.pdf. Accessed on: 2018-7-02.

- Blakemore RJ (2009) Cosmopolitan earthworms – a global and historical perspective. Chapter 14 in:. In: Shain D (Ed.) Annelids as Model Systems in the Biological Sciences.John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,New York, NY.

- Non-native invasive earthworms as agents of change in northern temperate forests.Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment2:427‑435. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0427:NIEAAO]2.0.CO;2

- Alaska Invasive Species Conference.Fairbanks, Alaska,October 26-28, 2010. https://doi.org/10.7299/X7JQ116Z

- Alaska Sustainable Agriculture Conference.Fairbanks, Alaska,March 5, 2015. URL: https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/ Bowser_ML_2015-03_earthworms.pdf

- Human-facilitated invasion of exotic earthworms into northern boreal forests.Ecoscience14:482‑490. https://doi.org/10.2980/1195-6860(2007)14[482:HIOEEI]2.0.CO;2

- Modelling interacting effects of invasive earthworms and wildfire on forest floor carbon storage in the boreal forest.Soil Biology and Biochemistry88:189‑196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.020

- Do non-native earthworms in Southeast Alaska use streams as invasion corridors in watersheds harvested for timber?Biological Invasions13:177‑187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9800-1

- The unseen invaders: introduced earthworms as drivers of change in plant communities in North American forests (a meta-analysis).Global Change Biology23:1065‑1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13446

- Exotic earthworm community composition interacts with soil texture to affect redistribution and retention of litter-derived C and N in northern temperate forest soils.Biogeochemistry126:379‑395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-015-0164-6

- Earthworm species, a searchable database.Opuscula Zoologica (Budapest)43(1):97‑99. URL: http://opuscula.elte.hu/PDF/Tomus43_1/Csuzdi.pdf

- Molecular phylogeny and systematics of native North American lumbricid earthworms (Clitellata: Megadrili).PLOS ONE12(8):e0181504. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181504

- Dash MC (1990) Oligochaeta: Enchytraeidae pp 311-340. In: Dindal DL (Ed.) Soil Biology Guide.J. Wiley,New York,1349pp.

- Ecology of some earthworms with special reference to seasonal activity.The American Midland Naturalist66:61‑86. https://doi.org/10.2307/2422868

- Contributions to North American earthworms (Annelida: Oligochaeta). No. 3. Toward a revision of the earthworm family Lumbricidae IV. The trapezoides species group.Bulletin of the Tall Timbers Research Station12:1‑146.

- GBIF Occurrence Download. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.aefeba. Accessed on: 2018-5-16.

- GBIF Occurrence Download. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.bvgr9n. Accessed on: 2018-5-16.

- Changes in hardwood forest understory plant communities in response to European earthworm invasions.Ecology87:1637‑1649. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1637:CIHFUP]2.0.CO;2

- Hinzman L, Viereck LA, Adams P, Romanovsky VE, Yoshikawa K (2006) Climatic and permafrost dynamics in the Alaskan boreal forest. In: III FSC, Oswood MW, Cleve KV, Viereck L, Verbyla D (Eds) Alaska’s changing boreal forest.Oxford University Press,New York.

- Influence of invasive earthworms on above and belowground vegetation in a northern hardwood forest.The American Midland Naturalist166:53‑62. https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031-166.1.53

- Changes in fire regime break the legacy lock on successional trajectories in Alaskan boreal forest.Global Change Biology16:1281‑1295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02051.x

- A test of the ‘hot’ mustard extraction method of sampling earthworms.Soil Biology and Biochemistry34:549‑552. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(01)00211-5

- Influence of nonnative earthworms on mycorrhizal colonization of sugar maple (Acer saccharum).New Phytologist157:145‑153. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00649.x

- Phylogenetic assessment of the earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa species complex (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences.Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution52:293‑302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2009.04.003

- After the Ice Age: The return of life to glaciated North America.The University of Chicago Presshttps://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226668093.001.0001

- Biological invasions in soil: DNA barcoding as a monitoring tool in a multiple taxa survey targeting European earthworms and springtails in North America.Biological Invasions15:899‑910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0338-2

- BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (www.barcodinglife.org).Molecular Ecology Notes7:355‑364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x

- A DNA-based registry for all animal species: The Barcode Index Number (BIN) system.PLoS One8:e66213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066213

- The earthworms (Lumbricidae and Sparganophilidae) of Ontario.Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontariohttps://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.60740

- Reynolds JW (1995) Status of exotic earthworm systematics and biogeography in North America. In: Hendrix PF (Ed.) Earthworm Ecology and Biogeography in North America.Lewis Publications,Boca Raton, Florida.

- Terrestrial Oligochaeta (Annelida: Clitellata) in North America, including Mexico, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Bermuda.Megadrilogica12:157‑208.

- A checklist of earthworms (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae and Megascolecidae) in western and northern Canada.Megadrilogica17:141‑156.

- Earthworms (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae) in the Cook Inlet Ecoregion (115), USA.Megadrilogica21:104‑110.

- Ecological predictors and consequences of non-native earthworms in Kennebec County, Maine.Northeastern Naturalist24:121‑136. https://doi.org/10.1656/045.024.0203

- Exotic earthworm distribution in a mixed-use northern temperate forest region: influence of disturbance type, development age, and soils.Canadian Journal of Forest Research42:375‑381. https://doi.org/10.1139/x11-195

- Distribution and abundance of exotic earthworms within a boreal forest system in southcentral Alaska.NeoBiota28:67‑86. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.28.5503

- Description and significance of a fossil earthworm (Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae) cocoon from postglacial sediments in southern Ontario.Canadian Journal of Zoology57(7):1402‑1405. https://doi.org/10.1139/z79-181

- Of glaciers and refugia: a decade of study sheds new light on the phylogeography of northwestern North America.Molecular Ecology19:4589‑4621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04828.x

- Different dispersal histories of lineages of the earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa (Lumbricidae, Annelida) in the Palearctic.Biological Invasions18:751‑761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-1045-6

-

SimpleMappr, an online tool to produce publication-quality point maps.URL: http://www.simplemappr.net

- Terhivuo J, Saura A (2006) Dispersal and clonal diversity of North-European parthenogenetic earthworms. pp. 5-18 in. In: Hendrit PF (Ed.) Biological Invasions Belowground: Earthworms as Invasive Species.Springer, Dordrecht[ISBN978-1-4020-5429-7]. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5429-7

- Invasion patterns of Lumbricidae into previously earthworm-free areas of northeastern Europe and the western Great Lakes region of North America.Biological Invasions8:1223‑1234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-006-9018-4

Supplementary material

Combination of standardised sampling and opportunistic sampling earthworm occurrence data for Interior Alaska.