|

Biodiversity Data Journal :

General research article

|

|

Corresponding author:

Academic editor: Anu Veijalainen

Received: 15 Nov 2014 | Accepted: 26 Feb 2015 | Published: 27 Feb 2015

© 2015 Joko Pamungkas

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Pamungkas J (2015) Species richness and macronutrient content of wawo worms (Polychaeta, Annelida) from Ambonese waters, Maluku, Indonesia. Biodiversity Data Journal 3: e4251. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.3.e4251

|

|

Abstract

The aims of this research were to: (1) investigate the species richness of wawo worms, and to (2) analyze macronutrient content of the worms. Wawo worms were sampled using a fishing net on March 18th-19th, 2014, from Ambonese waters, Maluku. As many as 26 wawo species belonging to 5 families were identified. Palola sp. was identified as the most abundant species of wawo, followed by Lysidice oele, Horst 1905, Eunice spp. and nereidids. Results of the proximate analysis reveal that female epitokes of Palola sp. contain 10.78 % ash, 10.71 % moisture, 11.67 % crude fat, 54.72 % crude protein and 12.12 % carbohydrate.

Keywords

Wawo worms, species richness, macronutrient content, Polychaeta, Ambonese waters.

Introduction

Similar to Pacific palolo, wawo or laor are edible marine worms (Polychaeta, Annelida) that are consumed by natives of Ambon, Maluku. These animals swarm twice a year to reproduce, i.e. either in February and March (

To date, the species richness of wawo remains uncertain. This is because different scientists studied in different areas. For instance,

The aims of this study were to: (1) identify the species richness of wawo worms, and to (2) analyze macronutrient contents of the worms.

Material and methods

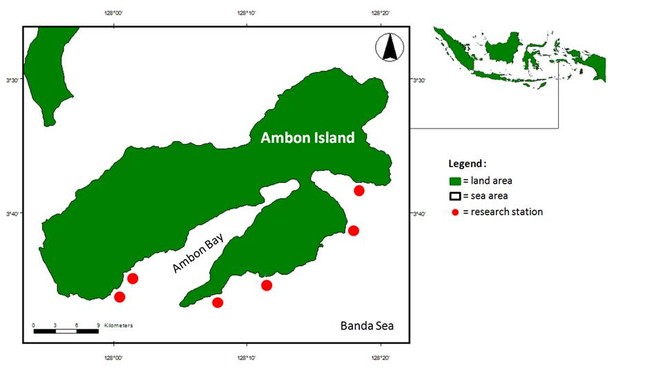

During the swarming time of wawo on March 18th-19th, 2014, wawo were sampled (Fig.

The proximate analysis, namely a quantitative analysis of a compound to determine the percentage of its constituents (i.e. ash, moisture, crude fat, crude protein and carbohydrate) was also applied to obtain information on wawo’s macronutrient. Female epitokes of Palola sp. were selected as samples for the analysis, and were collected from Alang waters on March 14th, 2009. The analysis was done at the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences, University of Pattimura, Ambon, with methods referring to

Ash was measured with the following procedure. An empty porcelain cup was first heated in a furnace at a temperature of 600˚C, cooled in a desiccator until room temperature is reached, and weighed (W1). The wawo sample (2 grams; wet weight; W2) was then placed on the cup. The cup with the sample was further heated to 600˚C, cooled in a desiccator until room temperature is reached, and weighed (W3). The heating process was repeated for half an hour until constant weight is reached. The following equation is used to calculate ash: (W3-W1)/ W2 x 100%.

Moisture was measured with the following procedure. An empty petri dish was first heated in an oven at a temperature of 105˚C for 3 hours, cooled in a desiccator until the room temperature is reached, and weighed (W1). The wawo sample (2 grams; wet weight; W2) was then placed on the dish. The dish with the sample was further heated in an oven at a temperature of 105˚C for 3 hours, cooled in a desiccator until the room temperature is reached, and weighed (W3). The heating process was repeated for several times until constant weight of sample is reached. The following equation is used to calculate moisture: (W3-W1)/ W2 x 100%.

Crude fat and protein were measured using Soxhlet and Kjeldahl method, respectively (

Results and Discussion

As many as 25 different species of wawo were discovered, including 3 species in the form of schizogamous epitokes and 22 species in the form of epigamous epitokes. The epigamous epitokes consist of 5 families, i.e. Eunicidae (7 species), Euphrosinidae (1 species), Lumbrineridae (3 species), Nereididae (9 species) and Scalibregmatidae (2 species) (Table

|

Types of Epitokes |

Species |

Stations* |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||

|

Epigamous |

|||||||

|

Family Eunicidae |

|||||||

|

Eunice sp. 1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Eunice sp. 2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Eunice sp. 3 |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Eunice sp. 4 |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Eunice sp. 5 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Eunice sp. 6 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Lysidice oele Horst, 1905 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Family Euphrosinidae |

|||||||

|

Euphrosine sp. |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Family Lumbrineridae |

|||||||

|

Lumbrineris sp. 1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Lumbrineris sp. 2 |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Lumbrineris sp. 3 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Family Nereididae |

|||||||

|

Ceratonereis singularis australis Hartmann-Schröder, 1985 |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Composetia marmorata (Horst, 1924) |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Neanthes cf. gisserana (Horst, 1924) |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Neanthes masalacensis (Grube, 1878) |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Neanthes unifasciata (Willey, 1905) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Nereis sp. |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

|

Pereinereis helleri (Grube, 1878) |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Perinereis nigropunctata (Horst, 1889) |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

Solomononereis marauensis Gibbs, 1971 |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Family Scalibregmatidae |

|||||||

|

Hyboscolex verrucosa Hartmann-Schröder, 1979 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

|

|

Scalibregmatidae sp. |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

|

|

Schizogamous/ Stolon |

|||||||

|

Family Eunicidae |

|||||||

|

Palola sp. |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Eunicidae sp. 1 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Eunicidae sp. 2 |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

|

Total Number of Species |

10 |

13 |

17 |

6 |

15 |

8 |

|

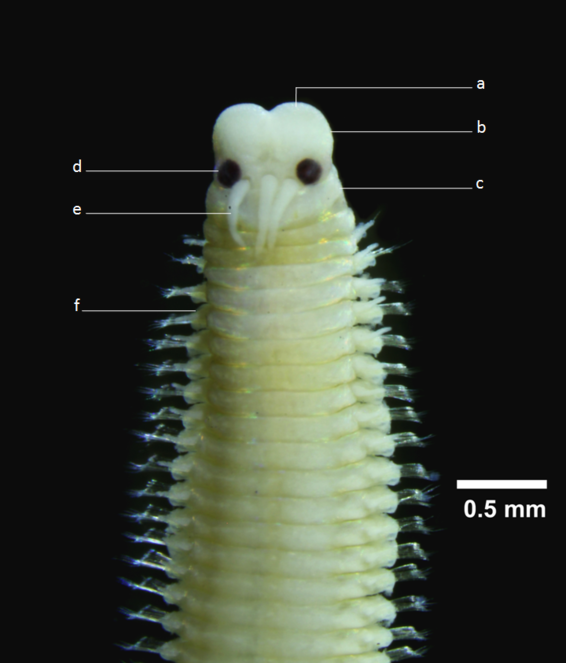

The most abundant wawo species at most stations is Palola sp. These animals are headless, relatively thin and have either pale yellow or green colors for male and female animals, respectively (Fig.

Palola sp. is also known as the islanders’ favourite as they smelt easily when sauted on a wok and thereby no longer look like worms. By contrast, bigger wawo that annually swarm in April are caught by only a few of locals due to their more unappetizing appearance. The later group of wawo, interestingly, has not been studied yet by scientists.

In this study, Lysidice oele Horst, 1905 (Fig.

The study also indicates that different stations generated different wawo species. This is most likely due to variations in habitat characteristics like differences in types, distribution and healthiness of coral reefs among stations. Nevertheless, this requires further investigations to prove. Differences in species richness among stations might also be due to variations in sampling effort.

Species number of wawo found in the present study (25 species) is higher than that of Martens and Horst’s studies (13 and 1 species, respectively). This supports the author's hypothesis that more study sites will yield more species of wawo due to differences in habitat characteristics. This also shows how diverse wawo are. In fact, wawo are also present in several different sites in Maluku waters such as Banda, Haruku, Nusalaut, Pombo, Saparua and Tual waters, but most of them are poorly or even unstudied (pers.obs.). This means that if we sample the animals in those unstudied sites, we are likely to discover both new species and new record species of wawo.

Besides high in species richness, wawo are also nutritious with 54.72% of their body is protein (Table

Conclusion

It is obvious from the study that the species richness of Ambonese wawo was considerably higher than that of previous studies as more research stations were included in the present study. This indicates how diverse wawo are, more than what has been known for decades. The study also confirms the locals' assumption that wawo are high in protein.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Hanung A. Mulyadi, Daniel D. Pelasula, Donna M. Siahaya and Wahyu Purbiantoro for their support to this study. Wawo samples from 6 different stations would never be possible to collect without help from my Ambonese colleagues, i.e. Abraham S. Leatemia, Eduard Moniharapon, Franky E. de Soysa and Robert Alik – thank you all. Constructive and critical comments from Dr. Christopher J. Glasby (Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin, Australia) towards the manuscript, as well as his help with the identification of wawo during his visit to Ambon on June 8th-14th, 2014, are also highly appreciated. Suggestions from Dr. Anja Schulze (Texas A&M University at Galveston, USA) improved the quality of the manuscript.

References

- Baoling W, Ruiping S, Yang DJ (1985) Taxonomic Section. The Nereidae (Polychaetous Annelids) of the Chinese Coast.China Ocean Press,Beijing. [InEnglish].

- Spawning periodicity and habitat of the palolo worms Eunice viridis (Polychaeta: Eunicidae) in the Samoan Islands.Marine Biology79:229‑236. [InEnglish]. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00393254

- Epitoky in Nereis (Neanthes) virens (Polychaeta: Nereididae): a story about sex and death.Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology149:202‑208. [InEnglish]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpb.2007.09.006

- Wawo and Palolo Worms.Nature69:582. [InEnglish]. https://doi.org/10.1038/069582a0

- Over de “Wawo” von Rumphius (Lysidice oele n.sp.).Rumphius Gedenkbook Kolon MusHaarlem1905:105‑108. [InDutch].

- Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists.13th Edition.Association of Official Analytical Chemists,Washington DC,1038pp. [InEnglish].

- Mas-senschwӓrmen des Südsee-Palolowurms (Palola viridis Gray) und weiterer Polychaeten wie Lysidice oele Horst and Lumbrineris natans n. sp. auf Ambon (Molukken; Indonesien).Mitt. Hamb. Zool. Mus. Inst.92:7‑34. [InGerman].

- Delicious! Marine Worms from Ambon Island, Indonesia.Marine Habitat Magazine2:35‑37.

- Radjawane TR (1982) Laor: Cacing Laut Khas Perairan Maluku. Lomba Karya Penelitian Ilmiah Remaja.Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia,Jakarta. [InIndonesian].

- Rumphius GE (1705) Vermiculi Marini. Wawo. D’Amboinische Rariteitkamer.Amsterdam. [InDutch].

- An account of palolo, a sea worm eaten in the Navigator Islands.Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London15:17‑18. [InEnglish].

- The palolo worm, Eunice viridis (Gray).Bulletin of The Museum of Comparative Zoology51:3‑22. [InEnglish].